Artfare: Aesthetic Profiling from Napoléon to Neoliberalism

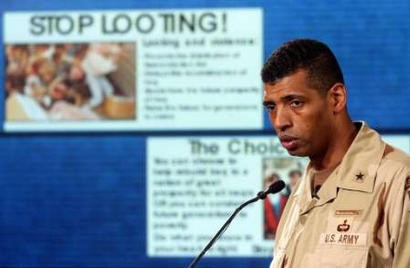

Fig. 2. Deputy curator Mohsen Hassan sits amidst the wreckage in the National Museum.

Available at Guardian.My goodness, were there that many vases?

Is it possible that there were that many vases in the whole country?1The Arts seek the land where laurels grow.2

On March 2, 2015, NBC ran a report titled, “ISIS Latest Radical Group to Destroy Ancient Art.” The report linked a video of ISIS adherents in Mosul’s museum to the Moghuls, the Nazis, the Khmer Rouge, and the Taliban, because all have “targeted not just innocent lives but also historic and cultural artifacts.” The report closed by quoting Thomas Campbell, director of the Metropolitan Museum of New York: “This mindless attack on great art, on history, and on human understanding constitutes a tragic assault not only on the Mosul Museum, but on our universal commitment to use art to unite people and promote human understanding.” Contrary to its talk of uniting humanity through art, the news report reveals that invoking “art” can classify peoples, rank them, and advocate oppression against those who do not meet an aesthetic profile. I call such a campaign to control the lives of others due to and through their compliance with art conventions, “artfare.”4

In this article, I trace two instances of artfare that have commenced from aesthetic profiling and resulted in a finders-keepers, buyers-owners system for governing not just cultural heritage, but swathes of humanity as well. From Napoléon in Italy to Bush in Iraq, aesthetic profiling prepares the way for artfare and regime change.

My concern for artfare developed when I was an art history major in college in the United States, participating in protests against the 1991 invasion of Iraq. Horrified by the slaughter of Iraqi lives, I was chagrined to discover how many of my acquaintances rationalized it on the grounds that contemporary Iraqis had “offered nothing important to humanity.” Two days after the American bombing of an Iraqi shelter that led to the incineration of 408 civilians, David Levine published a cartoon in the newspaper I read daily, The New York Times, which he called, “The Descent of Man.” Using a Darwinian schema, it showed that humans have been devolving since Charlton Heston, back through the primates and reptiles, to the lowest life form: Iraqi president Saddam Hussein. Some fellow art history students added that while Iraq was the “cradle of art,” it clearly was no longer relevant to art production, as evidenced by the lack of courses on our campus about any contemporary Iraqi or Arab or even Middle Eastern art. Personal and intellectual reasons relocated me in Lebanon by the time of the 2003 invasion. Now connected to the United States only through newspapers and talk shows, I noticed that once again aesthetic profiling—evaluating people for their actions on “art”—supported what I hear as Art Talk, a kind of political discourse that undergirds artfare and, by consequence, warfare.

Art Talk arises at moments of unclear political transition as a component of how observers, analysts, occupiers, and the occupied (unevenly) negotiate the terms of government. In the aftermath of the 2001 attacks, Mahmood Mamdani remarked upon the dependence of American political debate on “Culture Talk,” which he defined as “the predilection to define cultures according to their presumed ‘essential’ characteristics.”5 A way of explaining political crises, Culture Talk first isolates political actors into separate groups (say “Muslim fundamentalists” versus “average Americans”), attributes political disputes to essential ethnic differences (“they obey Islam; we love liberty”), and overlooks the history of encounters whereby groups interact and mutually produce each other’s political identities (for example, Mamdani notes that the Reagan regime supported and enabled the Afghani religious schools that trained “Islamic guerillas”).6 Culture Talk contributes to warfare by disentangling political actors’ long history of interaction, allocating blame for the current situation to one side only, and condemning that side for its purportedly substandard cultural characteristics. Culture Talk turns political problems into contests of merit, avoiding the political demands and their roots entirely. What I call Art Talk is a subset of Culture Talk: confining observations to how much people comply with aesthetic conventions, Art Talk similarly homogenizes people into distinct groups, dehistoricizes their political identities, and evaluates their claim to political participation by scrutinizing their actions on art.

While analysts of international conflicts tend to find their primary causes in economic, political, or religious realms, they generally marginalize the realm of cultural production. To explore that realm, my analysis is based on data from media that sought to explain and describe war-making to the audiences that fund, support, and contest warfare. Arjun Appadurai has argued that anthropologists may need to turn their attention from the imponderabilia of daily life to the “realisms” existing on and gaining legitimacy from larger, official scales such as global hierarchies and power dynamics: “The ethnographer needs to find new ways to represent the links between the imagination and social life.”7 Conventional field techniques were rendered impossible by my location in Lebanon during the invasion. Like the proto-typical armchair anthropologist, I could only view and review material mediated by journalists and editorialists. The press, however, is exactly the most commonly available medium in which the meanings of being Iraqi, American, occupier, and occupied were performed and imbued specific ideas about the Coalition occupation with social force.8 Thus, this essay was originally conceived during the 2003 events, and as a response to them, with the hopes of intervening in the way people like me, like my fellow students in art history, now professionals in the world, read the press and think about art, culture, and war.9 I offer it here to contribute to the discussion of the politics of art/the museum and our relationship to modern-day warfare and empire building.10

Art Talk, an Imperial Legacy

NBC report’s 2015 list of “militant groups and radical regimes” omitted major links between the seventeenth century Moghuls and the present day. Countering that opportunistic selectiveness, I focus on two intervening groups whose treatment of “historical and cultural artifacts” was paramount for establishing the importance of Art Talk in modern international relations: the first is Napoléon Bonaparte’s Italian Campaign in 1796, and the second is the invasion of Iraq in 2003 led by George W. Bush. Though Bonaparte and Bush are not usually grouped with “militant groups and radical regimes,” revisiting their episodes of looting and destruction will show how Art Talk concretizes in institutionalized dispossession. Certainly, the example of Napoléon underscores the fact that narratives about art have, for several centuries now, supported the practices of occupation and imperialism; more importantly, the eerie similarities between Napoléon’s and Bush’s ventures demonstrate that Art Talk is the legacy of occupation and imperialism, and not simply an unfortunate outcome, nor one innocent of their impulses. In other words, among the techniques of warfare is not only destruction of art and culture but also the production of art and culture, and concern for them. These, too, are deeply implicated in warfare.

Thus, I turn not to Napoléon’s Egyptian campaign, during which he may or may not have used the Giza Sphinx’s nose for target practice, but to the emperor-to-be’s earlier campaign that paved the way to Egypt.11 Upon seizing Rome, Napoléon systematically stripped the homes of Roman nobles of the statuary, paintings, and relics that today constitute the core of the Louvre Museum in Paris. He was the first conqueror to “legalize” looting by forcing the vanquished to sign contracts surrendering the work. Under banners with slogans like, “The Arts seek the land where laurels grow,” he paraded the material through Paris in 250 carts, in a “Festival of Liberty” that coincided with the anniversary of the fall of Robespierre, making the objects signify the “triumph over terror.”12 (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1. Fête de la Liberté, 9-10 Thermidor VI, Champs-de-Mars, Paris. Etching, 1798.

Reproduced in Patricia Mainardi, “Assuring the Empire of the Future,” Art Journal 48. 2 (1989), 155.

In response to international outrage at Napoléon’s actions, 37 prominent French artists justified the theft in the Gazette Nationale, avowing, “The Romans were lazy, superstitious barbarians who neither respected nor deserved their treasures.”13 Their recrimination consolidated the logic that how you treat hallowed objects evinces your mental acuity and, hence, your right to own art and be glorified by ownership of it. Notably, Roman voices were excluded from these French artists’ consideration of negotations over ownership on the grounds that their treatment of art evinced their backwardness. Art historian Patricia Mainardi calls this the “double authority” of art: beyond symbolizing claims to political superiority—when wrested as booty—it can actualize them—by bringing about new cultural configurations that, in turn, support claims to political and cultural dominance. Once the Capitoline Venus, Apollo Belvedere, Laocoon, and other great works of Roman pedigree were installed in the newly opened Louvre, Rome lost its role as the Mecca of artistic production and was relegated to being merely the “cradle of art.” Paris became the “city of light,” the obligatory training place for generations of artists until World War II. Like the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of New York from which Thomas Campbell condemned ISIS, is heir to this logic of imperial transfer and a living embodiment of art’s double authority (cf. Tomkins, Merchants and Masterpieces [1989], Felch and Frammolino, Chasing Aphrodite [2011]). What is more, Campbell’s condemnation of ISIS indicates that art has accrued a new authority, a moral-governmental one. This essay uses the lens of artfare to explain and explore the new authority.

Why is the looting of art an issue of such salience in the context of war, and not in the everyday context of visitors buying tickets to see (looted) art at the British Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris, or the Metropolitan Museum in New York? Likewise, how can one criticize, and intervene in, imperialism’s horrific muck without confronting the myriad ways imperialism becomes possible, ways that include talking about art and culture?14 Indeed, connecting the Napoléonic paradigm to contemporary conflicts shows that as part of the New World Order inaugurated by George W. Bush and instantiated in neoliberalism’s ever-widening reach, art has compounded a new valence to the duo detected by Mainardi. Particularly since the invasion of Iraq in 2003, “art” has become a means for imagining and managing populations and their right to political representation, especially at moments when governmental rule is adrift and justifications for regime change abound. If “warfare requires and inspires the invention of new practices of government,” as Nikolas Rose and Peter Miller argue, 15 then, I would argue that artfare is the control of people through the assessment and discipline of their aesthetic comportment. Nowadays, in addition to the ways in which appropriations of artworks in wartime serve to emblematize differences in military power and produce purported differences of cultural worth, conceptual appropriations—which occur in the form of media representation of art practices in conflict zones—allow for an aesthetic profiling that lends itself to governmental projects. Such projects require influxes of civilian resources (taxes, voter support) and control livelihoods while seeming merely to rate and reward aesthetic comportment. Indeed, conceptual appropriations that take as “art” other people’s lives and insert them into a dominant worldview, as Annabel Wharton shows in this edited collection, may propel a military project forward when momentum and belief had been faltering. News stories from Baghdad that talked of art in the bewildering moments between the end of the Baathist regime and the refusal of Iraqis to become uniformly pro-Western, provided a kind of clarity to the matter. Who was the liberator? Who was the oppressor? What costs were tolerable or necessary? My analysis of the Art Talk in these stories shows how the aesthetic profiling became a prime news agenda for determining what type of government “newly liberated” Iraqis “deserved.”

Aesthetic Profiling of Iraq: My Goodness, Were There That Many Vases?

Despite its historical and regional relevance, the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 is amazingly absent from the NBC 2015 list. Allegedly planned to extend only a few weeks, it was the consummation of a draconian siege of twelve years and has (so far) initiated another dozen years of devastating military occupation. Let it not be forgotten that in the first weeks after Baghdad’s fall in April 2003, media reports focused on the mysterious disappearance of the Iraq Museum collection—as many as 170,000 objects were reported vanished.16 For English readers, reports dealing with this loss, for which no one could be found directly responsible, overwhelmed reports of the damage inflicted by the preceding smart-bombing that deliberately did target innocent lives, in Iraqi hospitals, universities, bridges, and civil infrastructure generally.17 With detailed descriptions of the Museum’s evacuation reaching Anglophone audiences by April 11, officials at the U.S. military’s Central Command office found they had to address what an uncharacteristically bewildered Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, ruefully called, “suddenly the biggest problem in the world.”18 Responding to a journalist’s fear that the United States was culpable of failing to prepare for a proper military occupation, and the resulting “anarchy in Baghdad might wash away the [Iraqi] goodwill the United States has built,” Rumsfeld first insisted that images of “widespread looting” represented “liberated Iraqis celebrating their new-found freedom.”19 If Napoléon treated looting as an exercise of liberation, Rumsfeld glorified looting as a sign of Iraqis enjoying their “liberation.” Scores of news outlets quoted the Secretary of Defense’s assertion: “Freedom’s untidy, and free people are free to make mistakes and commit crimes and do bad things.”20 But when pressed to comment on military management, he explained that the looting was not so widespread. His proof was that Iraq was not so culturally rich:

The images you are seeing on television, you are seeing over and over and over, and it’s the same picture of some person walking out of some building with a vase, as you see it twenty times, and you think, “My goodness, were there that many vases?” (Audience laughter.) “Is it possible there were that many vases in the whole country?” It is a fundamental misunderstanding to see those images over and over and over again of some boy walking out with a vase and say, “Oh my goodness, you didn’t have a plan.”21

Rumsfeld reduced the systematic dismantling of Iraq’s government and social institutions to a single luxury item whisked off by a lone Iraqi boy. Turning the accusation of lack of planning on its head, Rumsfeld used the fact of the news clip’s repetition as proof that Iraqi society lacked an extensive civilization that would warrant a proper military occupation. The “vase remark” enjoyed even more replay in the U.S. media than had the actual clip. And just as the Secretary of Defense metonymically substituted the image of the vase for all social disorder in Iraq, the Anglophone international press quickly focused its concern for the armed and civilian re-appropriation of public and private assets in Iraq to images of the Iraq Museum. The fate of the Museum’s collection was soon at the forefront of the discussion of efforts to instill order in Iraq, as a first step toward determining its political future.

Enter Artfare

Crucially, Art Talk starts from the presupposition that art is a universal category that all humans have the capacity to make, recognize, and cherish. Thus, in his reflection on how “freedom” sometimes takes exacting forms, Tommy Tomlinson of the Charlotte Observer observed, “Everybody worried about all that ancient Iraqi art that was looted during the war. I wonder how much priceless Iraqi art was created during the past thirty years.” Where Rumsfeld could point to a single vase, Tomlinson could not name a single contemporary artist on par with Ray Charles or the director of Casablanca (his examples); hence he concluded that Iraqis should be grateful for their freedom, and beyond that Americans had no responsibility to Iraqis.22 Ignoring the cultural specificity and historical constructedness of the category “art,” let alone the requirement to overcome one’s personal ignorance, Tomlinson’s Art Talk divides the world into more or less art-loving cultures, with populations who comply with art’s requirements (for protection, appreciation, celebration, and so on) or fail to do so. The latter are those who do not deserve political voice; they are the very people who show up in NBC’s 2015 list of “militant groups and radical regimes” that have always existed but simply have no right to do so. Enter artfare.

Take this example, again from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York where Thomas Campbell would issue his condemnation a dozen years later. Eminent art-writer Calvin Tomkins penned an advance review of Art of First Cities, an exhibition slated to open in April 2003: “While looters were raping the Baghdad Museum’s peerless collection of Sumerian gold jewelry, stone and ivory and metal sculptures […] the Met’s curators were waiting anxiously for the arrival of promised loans of similar material from forty-eight other museums around the world.”23 By assembling inhabitants of Baghdad and employees of the Metropolitan around the category of “art,” Tomkins’s text renders the first group rapists and the second patient expectant fathers. This is aesthetic profiling at its apex. The resulting comparison demands that we look simply at how people act today on a set of objects whose proper way of being treated seems to be immanent to them. Little matter that many of the loans-to-be had been previously looted from Iraq by European archeologists and consuls and egregiously fragmented from vast temples, libraries, or royal dwellings.

But it’s not even art, right? The collection of the Iraq Museum was vaster than the contemporary definition of “art” addresses, the resulting cultural losses more complex, and the breadth of activity much broader. To call what was taken from the museum “art” misapprehends the problem. Still, the problem this essay tackles is the framework by which news stories appropriated objects to the category of art and mobilized cultural condemnations against political actors. In the immediate aftermath of the invasion of Baghdad, news and commentary sites across the Web came to be dotted with titles like “Art Falls Prey to War” (Guardian), “Iraqi Museum Looted of Priceless Art, Artifacts” (CNN), “Raiders of the Lost Art” (Daily Telegraph), “What Can Be Done to Recover Iraq’s Art?” (Washington Post), and “It’s Not the Oil, It’s the Art!” (Counterpunch).24 Implicitly or explicitly, in the first ten days of reporting, 27 percent used “art” to understand what was at stake in the emptying of the Iraq Museum, and in the second ten days 52 percent did so.25

I make this conclusion, and draw all my analysis of press coverage in this essay, from a reading of 130 English-language media accounts of the events at the Iraq Museum that appeared between April 10 and May 8, 2003 in major and minor news outlets accessible by the Internet and selected randomly from a pool of 2,820.26 I tried to cull from a range of writing genres, including editorials individualized for local audiences, semi-scholarly analyses of the Iraq Museum, and much briefer AP-based reports that were infinitely reproducible. Regarding the latter, while I consider the reproducibility telling in itself, I did not count such reports more than once toward the statistical analysis of the pool of 2,820.

Art Talk and the Creation of Presence

Reportage played a pivotal, but extremely restricted, role in the 2003 war. Audiences who read the stories from the Iraq Museum appearing in dailies serving the populations of the Coalition countries were called to become long-term military occupiers, tax-paying funders of a tutelary government, and economic beneficiaries of Iraq’s oil resources. Stories of Iraqi lives, politics, and material conditions were the medium by which readers could consider their optimum involvement. Yet, an unprecedented degree of military censorship controlled information about the war and occupation. Journalists who wanted to reach the battlefield had to sign on to a 50-point program of reporting rules, to “embed” themselves with troops, and to submit all stories to military authorities’ inspection.27 Unembedded journalists had no way of accessing transportation to news sites or broadcast facilities, and media in coalition countries were generally disinclined to disseminate their reports.28 Thus, when Baghdad was invaded, no live footage streamed from the Iraq Museum. Reports were constructed in the aftermath, relying heavily on alleged eye-witnesses, interviewed under the watch of military-minders, and funneled through CENTCOM censorship. In such reports, Art Talk worked by focusing news reports’ handling of the invasion’s ambiguities in ways that contributed to what anthropologist Edward Schieffelin calls, “the creation of presence” to which audiences could respond.29

Strikingly, nearly all (97 percent of the 130 reports analyzed) spoke of “looting” at the Iraq Museum.30 Expectations derived from military history—the longer version of NBC’s list—certainly informed usage of the term “looting,” yet neither direct knowledge of the events nor authorities supported it. As we have seen, even before the Iraq Museum hit the headlines, CENTCOM officials attempted to avoid the term, for the aspersions it cast on their ability to manage Iraqis.31 Moreover, as opposed to “re-appropriating” or “reclaiming,” “looting” implies a difference of identity between the taker and the owner. Who were the people plundering, and how did they relate to the owners? Whereas Napoléon announced his theft, inventoried the objects, claimed a cause, and declared their destination, no responsibility arose for the Iraq Museum: the perpetrators were anonymous, the objects removed were unlisted, the cause unclear, and the destination uncertain. With the “looting” and “art” frames firmly fixed around the unseen events, the questions reporters came to ask foregrounded the perpetrators’ identity as the key to understanding both the cause and outcome of their actions. Within this frame, the material form of the stories themselves deserves careful scrutiny, from syntax and metaphor to content and context.

First, many reports adopted an intimate perspective enhancing a sense of direct access to scenes that had not been available to cameras. Close verbal descriptions put the reader’s emotional reactions literally on the spot. “Eye-witness testimony” reconstructed events in minute-by-minute detail, and verbs in gerund form stretched the climactic moments as if still occurring before the eyes of the audience. Frequently, the sources blurred so the reporter’s voice provided seamless narration that, despite distance in space and time, could infer intent:

The looters had gone from shelf to shelf, systematically pulling down the statues and pots and amphorae of the Assyrians and the Babylonians, the Sumerians, the Medes, the Persians and the Greeks and hurling them on to the concrete. Our feet crunched on the wreckages of 5,000-year-old marble plinths and stone statuary and pots…32

A dozen looters roamed undisturbed among broken and overturned statues that littered the ground floor of the sprawling National Museum of Iraq, according to Agence France-Presse. Two men were seen hauling away an ancient door frame. Empty wooden crates were scattered across the floor.33

Muhammad said he went into the street in the Karkh district, a short distance from the eastern bank of the Tigris, about 1 p.m. on Thursday to find American troops to quell the looting. By that time, he and other museum officials said, the several acres of museum grounds were overrun by thousands of men, women, and children, many of them armed with rifles, pistols, axes, knives, and clubs, as well as pieces of metal torn from the suspensions of wrecked cars. The crowd was storming out of the complex carrying antiquities on hand carts, bicycles and wheelbarrows and in boxes. Looters stuffed their pockets with smaller items.34

Looters smashed glass display cabinets to grab what remained and began hitting the heavy items with iron bars, knocking heads off stone sculptures. Many seemed more intent on vandalism than looting.35

Second, the syntax of stories heightened the sense of the perpetrators’ disposition as antithetical to basic social values. Recurrent adjectives for the (unseen) people who emptied the Iraq Museum described them as “frenzied,”36 “demonic,”37 and “grotesquely violent.”38 Vivid prose brought readers into the eye of the “storm of lawlessness”39 that “swept much of the capital” before it “began to ebb.”40 Action metaphors frequently drew on environmental turbulence: waves, surges, and storms. These words placed the events in the pre-cultural realm and located the cause of the events at the Iraq Museum in destructiveness that knew no limits, and not, say, systematic, rational responses to political contingencies.

Third, news stories of the events at the Iraq Museum included “Iraqi voices” that could authenticate the reporter’s interpretation of events. Multiple reports incorporated the voice of Nabhal Amin, the museum’s deputy director: “‘This was priceless,’ she sobbed … ‘It feels like all my family has died,’ she wept. … ‘I cannot understand this,’ she said, ‘This was crazy. This was our history. Our glorious history. Why should we destroy it?’”41 Amidst a swamp of dumb debris, such voices consolidate a human presence. If we think about the difference between an event and a performance, in which actors play out meaning for an audience, the key to the latter is an assumption by actors and audience that all actions are communicative of ideas or qualities about the meaning being conveyed by the people designated as performers. While the emptying of the Iraq Museum had no designated performers, voiceovers by Iraqis staged in the aftermath seemed to secure actors’ responsibility for the meaning conveyed, in what anthropologist Richard Bauman identifies as a classic performance technique.42 Here, the testimony of Iraqi bystanders licensed certain audience interpretations, and carried them back to other Iraqi actors, as more journalists sought out similar voices. Similarly, photographers commonly positioned Iraqi observers in the midst of the Iraq Museum wreckage, while not accused of causing it, still implicated by it. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. Deputy curator Mohsen Hassan sits amidst the wreckage in the National Museum.

Available at Guardian.

Fourth, reports rarely contextualized the emptying of the Iraq Museum, which could have entailed detailing the crushed infrastructure and common coping mechanisms, describing the international network ready to receive antiquities without pedigrees, or discussing condoned and uncondoned theft by Coalition troops and journalists.43 Though some of this was glancingly mentioned in early reports, within a few days, reports isolated actors into separate groups, addressed behavior, and absented context, with the result that the emptying of the Iraq Museum came to present pure “art looting.” When reports provided historical context, it was exclusively regional. Thus, before the fall of Baghdad, Newsweek warned of looting, “This has been a feature of war in this part of the world since long before the seventh century BC.”44 Structured without an active subject, the sentence puts the “part of the world” in the place of human agency, facilitating the idea that looting is an indigenous, Mesopotamian epidemic.45

In sum, the majority of media accounts about the Iraq Museum implied that the disposition and motive of the perpetrators were fixed by their identity, formed fully in their national/ethnic/regional (67 percent), class (29 percent), or (less often at this early stage) sectarian (4 percent) background. The explanation was ultimately tautological, for such accounts extrapolated identity from the ways perpetrators (allegedly) removed material from the Iraq Museum. Thus, reporters sometimes distinguished the two kinds of Iraqis from their different approaches to (unseen) looting: “the angry and the poor, most of them Shiites, who were bent largely on destruction” and the “more discriminating, middle-class people who knew exactly what they were looking for.”46 Others occasionally went so far as to prove the involvement of non-Iraqis by noting their refined, high-tech behavior: “Witnesses have spoken of seeing well-dressed men with walkie-talkies at the scene, and of artifacts being transported away in orderly convoys of cars rather than over the heads of the crowd.”47 Clearly, you never just loot. The way you loot tells who you are. (Figs. 3 and 4)

Fig. 3. Less common coverage of the results of looting at the Iraq National Museum, BBC photo, distributed April 18, 2003.

Available at BBC.

Fig. 4. Widely distributed image of the results of looting at the Iraq National Museum Baghdad, distributed April 16, 2003.

Baghdad, Iraq

Turning Actions into Performances

When Napoléon deployed art’s double authority to transfer Rome’s political and cultural status to Paris, he rated and denigrated Romans’ cultural traits to justify his actions on art. By contrast, Iraq’s occupiers rated and denigrated actions on art to surmise Iraqi traits and appropriate governmental responses. This capacity to support aesthetic profiling is what I mean by a new authority for art, a moral-governmental one that supports artfare. By taking actions upon art objects to indicate context-transcending attitudes and probable socio-cultural trajectories, aesthetic profiling turns actions (even surmised ones) into performances in the sense defined by anthropologist James Peacock: deliberately meaningful displays of ideas and values.48 Thus, as a populace, Iraqis become culpable in their very way of being for the emptying of the Iraq Museum. If targeting historic and cultural artifacts is well entrenched in imperial history, then the Iraqi case was a unique instance of “cultural self-destruction,” according to editorialist Daniel Pipes, which indicated a “possibly unique Iraqi penchant for cultural self-hatred” and the “inherently violent quality of modern Iraqi society.”49 Occupation, Pipes offered, was going to be difficult, but clearly Iraqis could not govern themselves. Even writers less supportive of the invasion used the Iraq Museum case to take lessons about the Iraqi population and the type of governance to replace the Baathist regime. While some journalists simply wondered aloud “what the postwar collapse of order will mean,” others quoted Iraqi bystanders appealing for better governance, “We need the Americans here. We need policeman,” while still others noted possibly “more sinister motives in the US troops’ neglect.”50 All related the emptying of the Museum to the issue of governance. What the Iraqi replay of Napoléon’s “Festival of Liberty” shows us is how art’s authority went from double to treble.

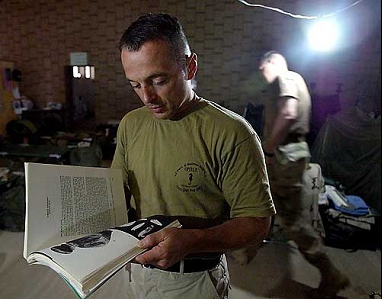

A mere week after several Basra-based sheikhs who called on occupation authorities to condemn looting were scorned by General Victor Renuart at CENTCOM for not appreciating it as a “festival of victory,”51 numerous news articles appeared documenting U.S. efforts to “create an environment” in which Iraqis could learn and choose to act better, including pamphlets the U.S. Army had produced to teach Iraqis that looting is bad (Fig. 5). In the frame of such stories, reports that neighborhood clerics and secular leaders were encouraging local residents to track down looted objects became performances of Iraqi civilian cooperation with, and legitimation of, the U.S. occupation, specifically in its capacity to tutor and civilize.52 Meanwhile, other stories detailed high-tech FBI and Interpol cooperation and arrests, Ahmad Chalabi’s successful “rescue” of Iraq Museum objects, and legal experts’ recitation of the international law dealing with looting. By May 1, a new hero took media center stage: New York lawyer and U.S. Marines Colonel Matthew Bogdanos. His alleged careful technique of “closer inspection” and sober reviewing of “the numbers” contrasted him succinctly from the “gibbering wreck” of a guard and the “hysterical,” sobbing Iraqi curator who could only weep helplessly at the site of her museum’s destruction.53

Fig. 5. American pamphlet to stop looting, as exhibited at CENTCOM press conference, April 16, 2003. Released by CENTCOM.

Available at CENTCOM. Photograph in public domain.

Not everyone quoted in the press agreed that the emptying of the Iraq Museum constituted a crime against Iraq’s national heritage. For some antiquities dealers based in New York or Basel, it showed, rather, that the notion of national inheritance had itself been a crime against the free market. In the frame of such stories, the looting in Iraq proved the validity of the art market’s liberal premises. The offers made in these stories to buy the works, to bestow measurable appreciation on them, allowed dealers to enact their understanding of money as an index of civilization, in contradistinction to the uncivilized who barter, or worse, steal. “The only thing that protects the artifacts right now is that they’re in the possession of someone who thinks he can get money for them.”54 Or, “the idea that theft might have been carried out by knowledgeable thieves lessened the likelihood that priceless artifacts would be melted down for the value of their material.”55 Writing in the Wall Street Journal, André Emmerich, a specialist in Pre-Columbian artifacts, argued that art’s well-being, like human well-being, is best advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade.56 In general, his invocation of the law of supply and demand may have reminded readers that the more art is destroyed in places like Iraq, the more the value of that held in Western museums and markets rises.

Conclusion: Neoliberalism’s Triumph

Ultimately, Anglophone reportage of the Iraq Museum consolidated a cultural agenda that superseded the particular case. By opening up what we can call the conceptual space of the “aesthetic delinquency,” the stories of the Iraq Museum clarified how people should act and feel in order to belong to moral humanity. One example from the BBC will suffice: “Art Gangs ‘Looted Iraqi Museum’” tells readers that “thousands of artifacts dating from the birth of civilization were stolen and damaged,” and blames the crime on “professional smugglers joined [by] opportunist civilians.”57 An inset simulating a police poster lists specific items “presumed missing.” An account of the recovery efforts undertaken by international organizations and professionals at European and American institutions follows. Clues to the commission of the theft, such as the use of keys, and mapping of common black market trade circuits led to the UNESCO director general’s call for a “heritage police” and an antiquities trade embargo. The article closes by mentioning the establishment of a “special fund for Iraqi cultural heritage” and an informational website. This media space produces the performance of characters who deal with the “disaster” in rational, practical ways and channel their anger into innovative, technology-using solutions. “Looting art,” as materialized in the Anglophone press in the aftermath of the invasion of Iraq, enabled, dialectically, respondent actions that contributed to the formation of a technologically savvy, self-possessed, law-abiding, and statue-uprighting identity for readers wondering how to think of themselves as part of the occupying public.58 (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6. Colonel Matthew Bogdanos in the act of calm inspection.

Photograph in public domain.

Art Talk turns discussion of the preservation or transformation of objects into talk about the identification, evaluation, and management of people. The frame of Art Talk confines all consideration of people’s behavior to their ability to comply with the (apparently immanent) demands made by objects (and not politics) on them. Their failure to respond appropriately to “not just innocent lives but also historic and cultural artifacts,” as NBC put it, renders them “mindless” creatures who attack not only “great art” and “history” but also “human understanding.” People who act “wrongly” on art—hold it inappropriately, place it in the wrong storage, treat it with reprehensible notions of ownership—become, in news stories based on Art Talk, populations who stand outside moral humanity. I use “population” in the Foucauldian sense of a conglomerate of bodies brought together through imposed techniques rather than a joint project that can represent itself, because Foucault explored the connection between governance that takes its goal to manage populations and neo-liberalism.59

Calling the Anglophone news reactions to it “Art Talk” does not deny the reality of what transpired. Rather, it directs our attention to the way this mediation, in turn, worked upon life conditions for all agents in the performative arena. This is most apparent in the role given in such accounts to the international art market, which thrives on the notion of art as portable alienable objects. Tellingly, while Iraqi national collections of material wealth were fragmented and scattered because, as Rumsfeld clarified for interviewer Tim Russert, “there are people who do bad things,”60 all news writers took it for granted that the international market for rare, ancient objects would receive an influx of new art objects. And it did.

Indeed, if anyone emerged victorious from the void of the Iraq Museum, it was neo-liberalism. Unlike earlier loot, material taken as “art” in the New World Order fills not museum halls but shopping malls, auctions, and websites of e-commerce, as reports from the Iraq Museum duly noted. While the “looting of Baghdad” did not distinguish between plunderer and plundered, it did separate the roles between those who take “art” improperly (without paying) and those who take it properly (via the market), or between those who use it improperly (for commercial gain or dictatorial dominance) and those who use it properly (in public, metropolitan collections). Unlike Napoléon’s parade, presentation of the “looting” from the Iraq Museum did not link supply and demand but rendered visible only the supply side. Because there was no officially declared destination for the museum contents but only educated guesses, its dispersal emerged in these reports as the simple working of market forces.

The fact that months and years later news reports scaled back their measurements of the damage to the Iraq Museum cannot undo the way Art Talk became a tool for explaining events and responses in those heady days when the world watched the fall of Saddam Hussein and debated the building of post-invasion Iraq. Art Talk isolates people’s actions on art from their socio-political contexts, determines who they are by how they act on art, attributes their behavior to a cultural trait (or rather, deficiency), and condemns an entire populace accordingly. To evaluate this I began my essay not with Napoléon’s famous (if imputed) instances of destruction in Egypt but rather his “production” in Italy of aesthetic profiling that justified his looting for the Louvre and boosted a supposedly self-evident category of art, whose legacy we live with today. The results of Napoléon’s artfare were decisive for art production and devastating for Italian careers and treasuries: No subsequent Italian art movement attained the stature of post-Napoléonic French art. Napoléon’s aesthetic profiling became self-fulfilling. In August 2015, Rijin Sahakian announced the closure of Sada, an arts facility center she had founded in 2010 in Baghdad to provide infrastructure for art production.61 Before the U.S.-led siege and invasion, Iraq had one of the best art education systems in the world. Rumsfeld’s joke about the relative rarity of Iraqi vases haunts the Iraqi art world and the world that believes in art. It reminds us of the teleology of the process of Art Talk, aesthetic profiling, and artfare.

Acknowledgements: The kernel of this essay was written in April–June 2003 amidst the posting of reports from the Iraq Museum, and it appeared in Arabic under the title “The Most Polished Cultural Imperialism: The Fragmentation of Iraq’s National Heritage,” in Al-Adab 51 (5-6): 4–11. Subsequently the essay developed through audience input following presentations at the “Art and War” panel that I co-organized with Jessica Winegar at the Middle East Studies Association meetings in 2005 and the American Anthropological Association meetings in 2006. I gratefully acknowledge the input of Jessica Winegar, Francesca Merlan, and Munir Fakher Eldin, as well as the research assistance of Heghnar Yeghiayan. The essay’s current instantiation owes its improvements to the intercession of Nasser Rabbat, Pamela Karimi, and Aggregate’s blind reviewers.

Related Material:

✓ Double-anonymously peer reviewed

Kirsten Scheid, “Artfare: Aesthetic Profiling from Napoléon to Neoliberalism,” Aggregate 4 (December 2016), https://doi.org/10.53965/SSIJ6418.

- 1

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, addressing journalists on April 11, 2003. See Office of International Information Programs, Pentagon News Briefing, U.S. Department of State, April 11, 2003, accessed April 24, 2003, http://usinfo.state.gov.

↑ - 2

Banner preceding a procession in 1798 of sculptures and paintings wrested from Rome by Napoléon Bonaparte and delivered to France. See Patricia Mainardi, “Assuring the Empire of the Future,” Art Journal 48.2 (1989): 155–167. Citation from page 158.

↑ - 3

Ambika Kandasamy, “ISIS Latest Radical Group to Destroy Ancient Art,” NBC News, March 2, 2015, accessed September 4, 2015, http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/isis-terror/isis-latest-radical-group-destroy-ancient-art-n315451.

↑ - 4

The term “artfare” arose in discussion with Peter Lagerquist, and I gratefully acknowledge my debt to him.

↑ - 5

Mahmood Mamdani, “Good Muslim, Bad Muslim,” American Anthropologist 104.3 (2002): 766–775. Quotation from page 766.

↑ - 6

Ibid., 770–772.

↑ - 7

Quoted in Keith Brown, “Macedonian Culture and Its Audiences,” Ritual, Performance, Media, ed. Felicia Hughes-Freeland (London: Routledge, 1998), 160–176. Quotation from page 161.

↑ - 8

Taking the United States and the United Kingdom as the most prominent members of the Coalition, and their publics as preeminent among communities called on to support the war, this paper therefore focuses on the Anglophone press in the immediate aftermath of the war and not on German, French, Spanish, or Arabic, the main languages of the other Coalition partners.

↑ - 9

A kernel of this paper appeared in Arabic in “Al-imbiriyaliyya fi akhir tajalliyatiha al-thaqafiyya: tashthiya al-turath al-watani al-`iraqi,” Al-Adab 51.5-6 (2003): 4–11.

↑ - 10

I thank Aggregate’s blind reviewers for their help formulating this contribution.

↑ - 11

For detailed and varied accounts concerning the destruction of the sphinx’s nose, see, “The Great Sphinx’s Nose: Who Is Responsible?” in Nile Magazine, ed. Jeff Burzacott (May-June 2015): 24–33, accessed August 10, 2016, http://go.epublish4me.com/ebook/ebook?id=10083847#/0.

↑ - 12

Mainardi, “Good Muslim, Bad Muslim,” 158.

↑ - 13

Ibid., 156.

↑ - 14

I thank editor Pamela Karimi for pushing me to extend Art Talk to this issue.

↑ - 15

Nikolas Rose and Peter Miller, “Political Power beyond the State: Problematics of Government,” The British Journal of Sociology 43 (June 2, 1992): 173–205. Quoted from page 178.

↑ - 16

Though the figure was later reduced to 15,000, initial reports commonly estimated 170,000. See for example, John Burns, “Pillagers Strip Iraqi Museum of Its Treasures,” New York Times, April 12, 2003, accessed April 15, 2003, http://www.nytimes.com/2003/04/13/international/worldspecial/13BAGH.html.

↑ - 17

I began this research as a regular news reader in April 2003, that is after the ground invasion which followed intense aerial bombing. The mainstream media’s bias against critical scrutiny of the results of Coalition bombing (i.e. the massive civilian death toll, the targeting of infrastructure to cripple civilian life, and the type of armaments used) has since been amply demonstrated in the literature (e.g. Aday 2005, Dimitrova et al 2005, Fahmy and Daekyung 2008, Schwalbe 2006). The government-friendly self-censorship was so obvious that civilian groups immediately started their own monitoring, leading to organizations like Iraq Body Count. A related bias characterizing post-invasion reporting prioritized news about the Museum and ignored other infrastructural damage. To test my hypotheses about this latter trend, I conducted Internet news searches in May 2003, using Google News. Of the 94,000 articles in English that mentioned “Iraq” between April 30 and May 8, 2003, 7,060 mentioned “looting,” with 2,820 focusing on the Iraq Museum as opposed to a mere 13 focusing on the looting of Iraq’s hospitals.

↑ - 18

See Office of International Information Programs, April 11, 2003.

↑ - 19

Ibid.

↑ - 20

Just one example, Sean Loughlin, “Rumsfeld on looting in Iraq: ‘Stuff happens,’” CNN, April 12, 2003, accessed September 26, 2015, http://edition.cnn.com/2003/US/04/11/sprj.irq.pentagon/.

↑ - 21

Ibid.

↑ - 22

Tommy Tomlinson, “Culture Has a Way of Breaking Out,” Charlotte Observer, May 4, 2003, accessed May 4, 2003, http://www.charlotte.com/mld/observer/news/local/5781641.htm.

↑ - 23

Calvin Tomkins, “First Cities,” New Yorker, April 28, 2003, accessed May 11, 2003, http://www.newyorker.com/talk/content/?030505tatalktomkins.

↑ - 24

Donald MacLeod and David Walker, “Art Falls Prey to War,” The Guardian, April 15, 2003, re-accessed May 20, 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/apr/15/iraq.internationaleducationnews; Beth Nissen, “Iraqi Museum Looted of Priceless Art, Artifacts,” CNN, April 13, 2003, accessed March 19, 2008, http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0304/13/se.04.html; “Raiders of the Lost Art,” Daily Telegraph, April 22, 2003, accessed May 4, 2003, http://www.indybay.org/news/2003/04/1603042.php; Irene Winter, “What Can Be Done to Recover Iraq’s Art?” Washington Post, April 27, 2003, accessed March 19, 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A39954-2003Apr25?language=printer; David Vest, “It’s Not the Oil, It’s the Art!” Counterpunch, April 25, 2003, accessed April 25, 2003, http://www.counterpunch.org/2003/04/23/it-s-not-the-oil-it-s-the-art/.

↑ - 25

Some were explicit, using the term “art” to refer to the Iraq Museum objects. Others imposed the framework implicitly, assigning the arts correspondent to the story, locating the article in the arts section, interviewing art experts or art dealers, or discussing the art market as the ultimate destination of the stolen objects.

↑ - 26

Many of the items I studied were published in multiple locations, meaning they constitute probably closer to 10 percent of the total published. Given my interest in the impact that media framings had on the range of actions conceivable at the time of the invasion, I do not deal with more recent responses. Likewise, I do not take up articles appearing in the Arab press at the time.

↑ - 27

See Deepa Kumar, “Media, War, and Propaganda: Strategies of Information Management during the 2003 Iraq War,” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 3 (March 1, 2006): 48–69.

↑ - 28

Ibid, 61–62.

↑ - 29

Edward Schieffelin and Felicia Hughes-Freeland, eds., “Problematizing Performance,” in Ritual, Performance, Media (London: Routledge, 1998), 194–207. Cited from page 194.

↑ - 30

38 percent of the accounts sampled had “loot” in their title, and another 59 percent used the term in their text. Only 3 percent made no use of the term at all.

↑ - 31

Already on April 9, 2003, the day U.S. troops captured the Iraqi capital, Brigadier General Vincent Brooks answered a journalist’s question about how to make sense of “a lot of pictures today of looting in Baghdad” by redirecting attention from the objects being whisked around the city to the emotions and cognitive processes behind the actions: the pictures showed “a lot of jubilation, and people who have long been oppressed for years and years having choices.” See CENTCOM, “Operation Iraqi Freedom Briefing,” April 9, 2003, accessed May 9, 2003, http://www.centcom.mil/CENTCOMNews/Transcripts/20030416.htm.

↑ - 32

Robert Fisk, “A Civilization Torn to Pieces,” Independent, April 13, 2003, accessed April 15, 2003, http://webmedia.newseum.org/newseum-multimedia/tfparchive/2003-04-12/pdf/GAAJC.pdf, emphasis added.

↑ - 33

Mike Toner, “Museum Antiquities Looted,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, April 12, 2003, accessed April 15, 2003, http://www.ajc.com/news/content/news/iraq/0403/12irantiquities.html, emphasis added.

↑ - 34

Burns, “Pillagers,” emphasis added.

↑ - 35

Art Newspaper. April 20, 2003, accessed April 20, 2003, http://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/article.asp?idart=10983, emphasis added.

↑ - 36

Burns, “Pillagers.”

↑ - 37

Jeremy Seabrook, “New Vistas: Freedom to Loot,” Statesman, May 4, 2003, accessed May 4, 2003, http://www.statesman.net/page.news.php?clid=4&theme=&usrsess=1&id=11809.

↑ - 38

A. N. Wilson, “Looters Need a History Lesson,” This Is London, April 14, 2003, accessed May 29, 2008, http://www.thisislondon.co.uk/news/article-4338685.

↑ - 39

Lowell Ponte, “Thieves of Time,” FrontPage Magazine, April 14, 2003, accessed April 15, 2003, http://frontpagemag.com/Articles/ReadArticle.asp?ID=7267.

↑ - 40

Burns, “Pillagers.”

↑ - 41

Tom Engelhardt, “Plundering History,” Mother Jones, April 15, 2003, accessed April 15, 2003, http://www.motherjones.com/news/warwatch/200316/we35901.html#one.

↑ - 42

Richard Bauman, Verbal Art as Performance (Rowling, MA: Newbury House, 1977).

↑ - 43

See, for example, Jerry Seper, “Looting Probes Eyes Journalists,” Washington Times, April 24, 2003, A01; also, Seabrook, “New Vistas;” and “Raiders of the Lost Art.”

↑ - 44

Melissa Liu and Anne Underwood, “Babylonian Booty,” Newsweek, March 24, 2003, accessed April 15, 2003, http://www.newsweek.com/babylonian-booty-132667.

↑ - 45

In fact, the incredible effort that occupation troops made to understand looting as a sign of Iraqi identity went virtually unnoticed in the Anglophone press. Four men accused of stealing arms were apprehended by American soldiers, stripped, and paraded naked through Baghdad with the name for the paradigmatic thief “Ali Baba” penned onto their chests. See (in Danish) Line Fransson, “Vi tok klærne og brente dem før vi dyttet dem ut med ‘tjuv’ skrevet på brystet,” Dagbladet, April 25, 2003, accessed May 4, 2003, http://www.dagbladet.no/nyheter/2003/04/25/367175.html; see also, Amnesty International, “Iraq: Stripped Naked and Humiliated by US Soldiers.” AI Index, April 25, 2003, accessed May 4, 2003, http://web.amnesty.org/library/index/engmde140972003.

↑ - 46

Andrew Gumbel and David Keys, “US Blamed for Failure to Stop Sacking of Museum,” Independent, April 14, 2003, accessed April 15, 2003, http://news.independent.co.uk/world/middle_east/story.jsp?story=397004.

↑ - 47

“Raiders of the Lost Art.”

↑ - 48

Felicia Hughes-Freeland, “Introduction,” in Ritual, Performance, Media, ed. Felicia Hughes-Freeland (London: Routledge, 1998), 1–28, 6.

↑ - 49

Daniel Pipes, “An Iraqi Tragedy,” New York Post, April 22, 2003, accessed May 14, 2003, http://www.nypost.com/postopinion/opedcolumnists/73942.htm.

↑ - 50

See Toner, “Museum Antiquities;” Fisk, “A Civilization Torn;” and Gumbel and Keys, “US Blamed,” respectively.

↑ - 51

CENTCOM Operation Iraqi Freedom Briefing, April 10, 2003, at www.centcom.mil, accessed April 25, 2003, http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/library/news/iraq/2003/iraq-030410-centcom01.htm.

↑ - 52

General Brooks explained, “Distribution of leaflets and handbills … are also having a favorable effect at this point. Emerging leaders have also joined the call for looting to cease.” See CENTCOM Operation Iraqi Freedom Briefing, April 16, 2003, accessed April 25, 2003, http://www.centcom.milCENTCOMNews/Transcripts/20030416.

↑ - 53

The quoted phrases appear respectively in: Bill Glauber, “Recovery of Looted Iraqi Treasures Is Slow,” Chicago Tribune, May 8, 2003, accessed May 9, 2003, http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/nationworld/134699073_museums08.html; P. McGeough, “Rich Past Stripped as Future in Tatters,” Sydney Morning Herald, April 14, 2003, accessed April 20, 2003, www.smh.com.au/articles/2003/04/13/1050172478179.html; Glauber, “Recovery;” Engelhardt, “Plundering History.”

↑ - 54

Joe Bob Briggs, “Burning Museum? Ho Hum,” UPI, April 15, 2003, accessed April 17, 2003, http://www.joebobbriggs.com/jbamerica/2003/jba20030415.html.

↑ - 55

St. Petersburg Times, “Museum Looting May Have Been Planned,” St. Petersburg Times, April 17, 2003, accessed April 20, 2003, http://www.sptimes.com/2003/04/17/Worldandnation/Museumlootingmay_ha.shtml.

↑ - 56

Andre Emmerich, “Let the Market Protect Art,” Wall Street Journal, April 24, 2003, accessed May 9, 2003, http://www.opinionjournal.com/la/?id=110003399.

↑ - 57

BBC editorial, “Art Gangs ‘Looted Iraqi Museum,’” BBC Online, April 17, 2003, accessed April 18, 2003, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/2955421.stm.

↑ - 58

The logic worked at subcultural levels, too: leftist American writers frequently separated their art-loving identity from that of the crass administration that, due to insensitivity, had “failed” to protect the global heritage represented by Iraqi art.

↑ - 59

Michel Foucault, “Governmentality,” in The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality, eds. Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon, and Peter Miller (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 87–107.

↑ - 60

Interview with Donald Rumsfeld by Tim Russert, “NBC Meet the Press,” NBC, April 13, 2003.

↑ - 61

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, “Calling It Quits: What Is the Future of Art Education in Baghdad?” Frieze 172 (June-August, 2015), accessed September 8, 2015, http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/calling-it-quits/.

↑