Spatial Practices of Dissidence: Identity, Fragmentary Archives, and the Austrian Resistance in Exile, 1938–1945

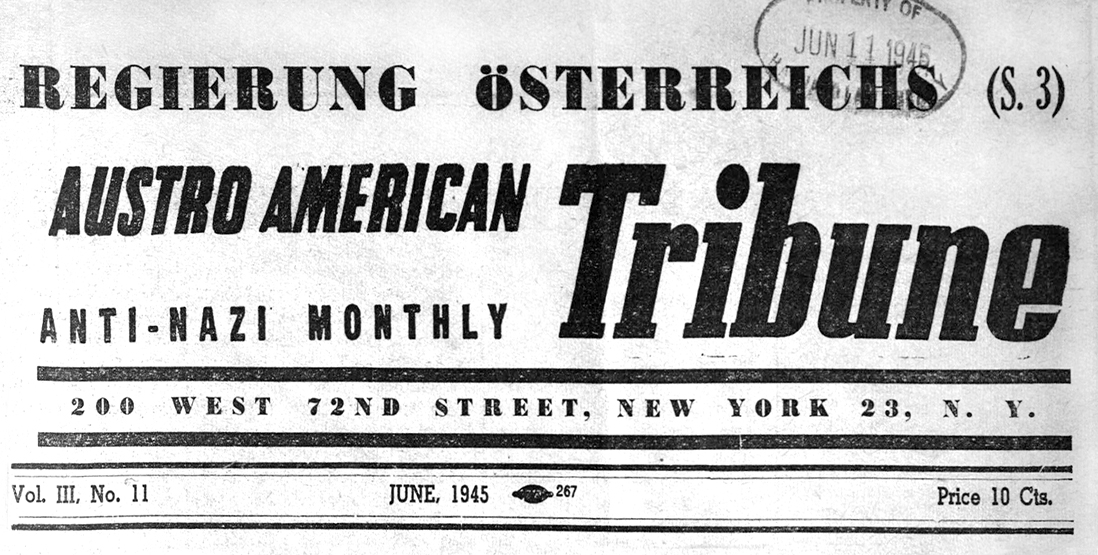

Cover page of the Austrian-American Tribune, September 1944.

Harvard Law Libraries.

A guesthouse,

an apartment,

a safe house.

An editorial office,

a cultural institute,

a farm.

A cover,

a font,

a translation.

A letter exchange,

an encrypted message,

or a single word.

Resistance in exile against the National Socialist regime was formulated in ordinary spaces. It materialized in mundane rooms, buildings, and landscapes, in private domestic settings and semi-public places. These spaces were clandestine and often temporary. They constituted the backdrop against which artifacts of dissidence, textual and visual, were created. In the following four coupled fragments, I illuminate sites of dissidence in emigration, exile, and internment. These spaces reflect what philosopher Günther Anders calls “years in motion,” time shaped by deep instability but also fleeting moments of permanence grounded in friendship.1 In these places, individuals and groups organized dissent and cared for one another. Theirs are stories of both suffering and defiance, or what historian Ernst Loewy understands as “the twinned character of exile.”2

Since the late 1960s, architectural historians have produced a body of scholarship about architecture during World War II and the period between the 1930s and 1945.3 Only in the last three decades, however, have methodologies emerged that highlight epistemologies of design and planning in exile; many of these histories have been, substantially influenced by literary studies.4 Where these critical exilic histories of architecture exist, they have often focused on cultural translations and how artistic production took shape under conditions of migration.5 Some have recorded how individuals experienced displacement and loss while others foregrounded the fragility of surviving records and artifacts.6 Recent scholarship has emphasized notions of in-betweenness in exile, in a distinct departure from earlier histories that have chronicled the spatial production of the Nazi perpetrators. As literary scholars Dörte Bischoff, Esther Kilchmann, and Christoph Gabriel point out, “formulating a claim to cultural belonging beyond claims to state power and territorial demarcation” was a main characteristic of exile and one that tracing it consequently demands.7

In this essay, I draw on this idea of belonging to highlight the instability of exile archives and the overlooked labors of resistance in architectural history, privileging a reading of manifold spatial practices over formal analyses of architecture.8 I use the term “spatial practice” to mark the significance of human agency and lived experience in architectural history, and to signal a confluence of spatial appropriation and living and laboring together. By assembling and interpreting a variety of places and objects as sites of dissidence—landscapes, cities, infrastructure, as well as letters, journals, woven artifacts, and the individual body—the essay oscillates between the scales of these labors. As such, I also focus on people and how they cared for each other and forged solidarity, friendship, and kinship under duress. Examining spatial and embodied manifestations of care and friendship helps move away from analyses of party organizations, hierarchies, and the histories of the oppressors, and toward multidirectional networks and identities. Relationships and embodied knowledge are a critical part of reconstructing architectural histories of exile, dissidence, and resistance.

The following fragments can be read dialogically, or they can stand on their own terms. Most are structured around individuals—among them architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and author Elisabeth Freundlich—or a group of well-acquainted people. Others follow strangers unfamiliar to one another but bound together in resistant work through the cities of Istanbul, Belgrade, Vienna, Paris, or New York. Their stories are presented partially to remind readers that histories of spatial practices of dissidence and exile are often impossible to know fully due to their unstable or entirely nonexistent archives. Readers should not expect total reconstructions of architecture, drawings, or floor plans. Blurry photographs, secret letters, fragments of textiles, or writings authored under pseudonyms are often the only remnants of dissident histories. Some of these histories are connected and show the intersection of peoples’ lives. Others expose competing historiographies.

1. Homes, 1938

A guesthouse,

Then temporarily safe at Hacı İzzet Paşa Sokak, Istanbul.

In Vienna,

48,000 Jewish homes seized.

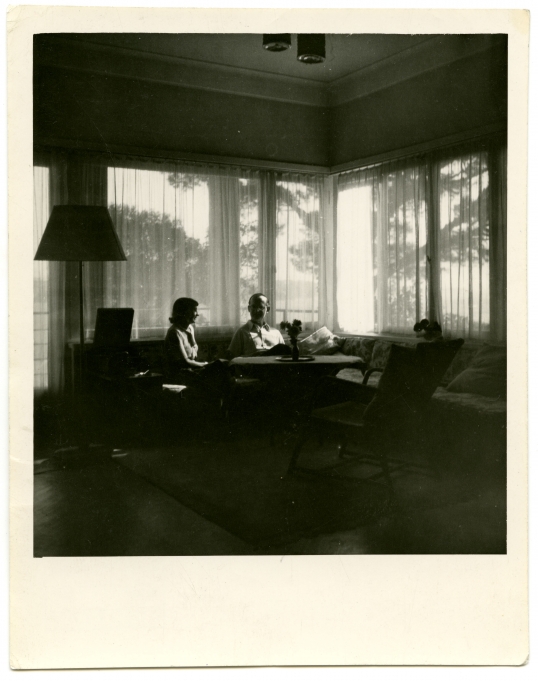

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s Guesthouse in IstanbulFig. 1. Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte at their apartment, Istanbul, 1940. Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky Papers, University of Applied Arts, Vienna, F-151. Private spaces, from residences to hotel rooms, were critical in the development of resistance strategies during World War II. Although photographs survive of Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s apartment at Hacı İzzet Paşa Sokak 28, her home in Beyoğlu, Istanbul, between 1938 and 1940, only one picture captures an approximation of what could never become fully conveyed in images: the dangerous labor of dissidence undertaken in ordinary spaces. The photo shows Schütte-Lihotzy and her husband, the architect Wilhem Schütte (1900–1968), seated on a sofa in a darkened room, in front of a light-filled balcony (fig. 1).9 Both architects were members of the Austrian Communist resistance in Istanbul. This image contrasts with others that show the couple sipping coffee on a sunny balcony overlooking the Bosporus (fig. 2).10 Over the course of two years, in the privacy of guesthouses, hotel rooms, and apartments, Schütte-Lihotzky, Schütte, and several others organized clandestine meetings in which political and architectural life overlapped.11 Schütte-Lihotzky later recalled that this was “a time of satisfying, meaningful work, a theoretical engagement with Marxism in direct relationship to resistance activity in Austria and the possibility for practical support.”12 The private spaces in which these activities were carried out were impermanent, but they provided the framework for oppositional efforts. Fig. 2. Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte at their apartment, Istanbul, ca. 1940. Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky Papers, University of Applied Arts, Vienna, F-138. How had Schütte-Lihotzky come to resistance labor? Between the mid-1920s and the mid-1930s she had enjoyed a relatively comfortable life in Austria, Germany, and the Soviet Union. Her design for the standardized Frankfurt Kitchen was implemented in ten thousand households by the end of the 1920s.13 In Moscow she worked on collectivized kindergartens and headed a division for educational institutions.14 Yet, between 1937 and 1938 she and her husband urgently searched for work in Paris and London after their visas expired in the Soviet Union. On the eve of the “Anschluss,” the Annexation of the Austrofascist State to Nazi Germany in March of 1938, German architect Bruno Taut (1880–1938) offered them secure positions in Istanbul.15 Because of the safety of these positions, Schütte-Lihotzky acknowledged that her life in Turkey was not an experience of “emigration” in the strict sense.16 She felt disheartened by the treatment of some of her colleagues at the Devlet Güzel Sanatlar Akademisi, the state academy of fine arts, who were considered minorities in Turkey and did not have the same legal rights. “It was the first time there, that I did not work in a collective,” she remarked later, contrasting the experience with her prior employment in Vienna, Frankfurt, and Moscow.17 In 1938 the political situation in Europe drastically worsened and Turkey restricted migration closing its borders entirely to Jewish people fleeing prosecution in Europe.18 In the same year Schütte-Lihotzky decided to join the clandestine Austrian Communist Party abroad.19 In domestic spaces in Istanbul, preparations for the possibility of active dissidence in Vienna began. Resistance cells abroad were limited to tightly knit circles of people, rarely numbering more than four or five. To avoid denunciations, political and national organizations, too, were kept strictly separate. Collaborative work was, nonetheless, essential and professional affiliations sometimes played an initial role in dissident work. Aside from her husband, Schütte-Lihotzky’s closest confidants in Turkey were the Chilean architect Victoria Maier Mayer (1914–2004) and the Austrian architect Herbert Eichholzer (1903–1943).20 Schütte-Lihotzky and Schütte, shared professional and social convictions with Eichholzer and Maier Mayer. Eichholzer, who had been tasked with leading the Austrian Communist resistance in Turkey, had arrived in Istanbul from exile in France after having been imprisoned in Austria for participating in the armed uprising against the Austrofascist regime. He lived and worked with several colleagues at the office and residence of Austrian architect Clemens Holzmeister (1886–1983), where he designed governmental buildings.21 Maier Mayer, who had been Holzmeister’s student in Vienna, joined the office in 1939 and lived, like Eichholzer, at Holzmeister’s home and studio in Tarabya, on the outskirts of Istanbul. A humanist and democrat by conviction and far from her home in Chile, Maier Mayer had been hard-pressed to leave Vienna after the “Anschluss” with Nazi Germany in 1938. Schütte-Lihotzky and Schütte’s temporary home in the guesthouse Şana in Kadıköyt, the mouth of the Sea of Marmara across the Bosporus, became the first place for early secret meetings for small groups. The financial stability Schütte-Lihotzky and Schütte enjoyed in their architectural profession, as well as their religious identity as Protestants, partly enabled their dissidence abroad. At Şana the group discussed and reviewed resistance tactics and debated the theoretical underpinnings of Marxism long into the night.22 The later apartment in Beyoğlu played a similar role. Located more centrally, in a neighborhood where many foreigners had settled between the Golden Horn and the Bosporus, the apartment was easy to access and allowed for inconspicuous connections with other expatriates.23 Schütte-Lihotzky recalled that in Istanbul, her political conscience was sharpened and she became a believer in a social framework through which a more democratic architecture could unfold.24 For Schütte-Lihotzky, Schütte, Maier Mayer, and Eichholzer, the two years in Istanbul and the friendships they formed there marked a shift from fashioning an architecture for the poor on behalf of municipalities to radical political work directed against the state. Domestic spaces became pockets of safety and privacy for tactical training in urban settings. Strategic discussions took place in hotel rooms and apartments before operations were carried out in the city. Eichholzer called upon the Istanbul group for assistance when high-ranking officials in the Communist Party of Austria sought safe passage to Moscow, where they would continue operations after 1939. Always at risk of surveillance or interception, the novice dissidents had to learn how to secure documents for safe transit. They were instructed how to navigate streets and administrative offices without being questioned by authorities, an activity first discussed in hotel rooms and apartments and then put to test in the metropolis. Often this labor required assisting high-ranking functionaries, with whom individuals in the group were acquainted only by pseudonym. Schütte-Lihotzky recalled securing passage aboard ship for a party functionary who was travelling with forged papers, an undertaking that involved careful planning as well as spontaneity and improvisation.25 Not every urban or private space, however, was adequate for resistance labor. The Holzmeister residence and office, for example, was no place to carry out radical clandestine work. Like Holzmeister himself, colleagues in the office were loyal to the proto-Christian Austro-Fascist state. Recent research has revealed that the office even sheltered a number of Nazi sympathizers.26 Denunciations from colleagues were a constant threat for Eichholzer and Maier Mayer, and the two likeminded friends developed a partnership, political and romantic, that deepened their commitment to the resistance.27 The office provided them with good but dangerous cover.28 From letters and photos, it is clear that balconies, living rooms, kitchens, and bedrooms provided a backdrop for laughter, dinners, and theoretical discussions, but also training for activities in the city and beyond. As dissidents were initiated into resistance labor, they were expected to complete small tasks in the city and eventually abroad. Indeed, training in the realm of the domestic was only preparation to fulfil the Communist Party’s call to fight for the “resurrection of an independent Austria.”29 This mandate was distinctly nationalist in nature and did not account for strategies that questioned notions of belonging beyond territorial bounds—which were especially critical for Jewish people and others who had become exiled or stateless. Expatriate residences, hotels, guesthouses, and temporary abodes were thus only one set of places where the initiation into the spatial practice of dissidence took place. Historians today agree that many resistance fighters underestimated the risks and demands of their political work.30 Yet, accounting for the political spaces and the activities carried out in them does much to illuminate the resilience and ingenuity of resistance fighters in the face of widespread surveillance. Rather than focusing on authored design ideas looking to dissident domestic spaces highlights an embodied, radical and insurgent domesticity in which courage was cultivated for a moment in time in the late 1930s.31 |

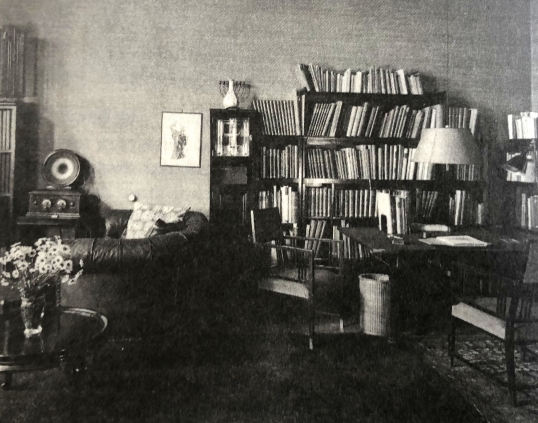

Elisabeth Freundlich’s Apartment in ViennaFig. 3. Elisabeth Freundlich’s room and study at her family’s apartment, Vienna, ca. 1935–1938. Elisabeth Freundlich, Die Fahrenden Jahre. Pictures of Austrian author and dramaturg Elisabeth Freundlich and her Vienna home are rare. Though her writing would later find its way into an archive, only a grainy reproduction of a photograph of her room survives today (fig. 3). With a desk and bookshelves, the picture portrays the home as an environment for contemplative work, but it was also one of encounter. Freundlich remembers the mid-1930s as a time of political organizational labor. Her workspace features two chairs in the fashion of the Wiener Werkstätte. Atop a cabinet, a menorah sits behind a vase.32 Daisies are placed on a side table, near an armchair and a record player. It was in this room where Freundlich’s political work in Vienna came into focus. Freundlich’s political consciousness had been shaped by her encounter with persistent anti-Semitism in early-1930s Vienna. Despite her standing in the city’s literary circles and her stellar credentials from the Universität Wien, she was unable to find employment when she returned to Austria in 1933 from her studies in Paris (figs. 4 & 5). In 1934, her father—a prominent and dedicated Social Democrat and president of the Arbeiterbank, a workers’ savings bank—was imprisoned by the Austrofascist regime. Placed under house arrest and prohibited from working, the family lost Freundlich’s childhood home and was forced to relocate to a smaller apartment. Her father’s persecution hardened Freundlich’s conviction to fight fascism at all costs and attuned her, early on, to the acute dangers of anti-Semitism. “Anti-Semitism was already virulent then,” she wrote of the political climate in early 1930s Vienna.33 Fig. 4. Elisabeth Freundlich in Paris, ca. early 1930s. Elisabeth Freundlich, Die Fahrenden Jahre. Freundlich’s encounters with loss, violence, and trauma compounded in 1938. The “Anschluss” meant the immediate and relentless assault on Jewish Austrians, through “widespread antisemitic actions and political violence.”34 British journalist George Eric Rowe Gedye (1880–1970) described the events of March 11 in Vienna: 35 In Vienna and the provinces plundering started that night… . Nearly every Consulate in Vienna is in possession of the details of hundreds of fully authenticated cases illustrating how this private plundering was carried out unchecked for many weeks. I know myself of cases where it was done with cynical courtesy, of others with utmost brutality, including the wanton wrecking of furniture, shooting up of mirrors and smashing of paintings… . Far worse was the plundering of the humbler Jews.36 The violent anti-Jewish November pogroms—euphemistically called “Kristallnacht” or the “Night of Broken Glass”—marked the systematic round up and deportation of Jewish people and the destruction of more than seven thousand Jewish businesses and 267 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria, and the region of Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia.37 In the months between March 1938 and April 1939, of more than seventy thousand apartments owned by Austrians of Jewish descent, it is estimated that between forty-five thousand and forty-eight thousand were seized by coordinated assaults and deportations.38 Holocaust historian Gerhard Botz writes that in Austria attacks against Jews were so pervasive and violent in the first days after the “Anschluss” that Nazi officials initially accused Communists and Social Democrats of the crimes to avoid unfavorable international press.39 Only days after the “Anschluss,” deportations of Jewish Austrians began. The Freundlich family was forced to flee Vienna on March 12, leaving almost all their possessions behind.40 Among her family members, Freundlich recalls that only she saw things clearly. Her father deliberated departing. “‘One doesn’t leave one’s friends in such a situation. They are going to need me,’” she remembers him stating. “I felt shabby and coarse, throwing his impotence in his face, but I didn’t have a choice… . ‘The Gestapo will find your files and then come and find you!’” she recalled.41 She was ultimately able to convince him to flee to Switzerland, where her aunt lived. Fearfully, the family boarded one of the last trains to Zurich the next day. “One is more than aware of the images of what would have awaited us,” Freundlich wrote. “The old people, crawling on their knees, scouring away with toothbrushes … amid gleeful looks and cat-calls from passersby, under the command of the new rulers… .”42 The events, after half a century, were etched into her mind with “undiminished clarity.”43 Fig. 5. Elisabeth Freundlich in Paris, ca. early 1930s. Elisabeth Freundlich, Die Fahrenden Jahre. In her autobiography, Freundlich noted that through political action she had begun to confront the trauma of displacement, alienation, and persecution in exile. After Switzerland, the family tried to find safe harbor in Paris. In the winter of 1938 and 1939, with her proficiency in French, Freundlich became an active participant in émigré organizations, humanitarian and cultural institutions, and peace initiatives. With other exiled writers in France, she founded the Cercle culturel autrichien (Austrian cultural circle) and the Ligue de l’Autriche vivante (League for a living Austria).44 In these two groups, political and cultural work converged in the organization of events and mutual aid. The groups addressed questions of belonging, which were important for Jewish people who, by emigrating, had been stripped of their citizenship. For a few months, Paris seemed like a place of safety, although it was impossible to find paid work. The photograph of Freundlich’s Vienna home thus reflects complex questions of identity, although they are not immediately legible. The picture is a glimpse into Jewish life in Vienna, but it also documents the displacement and destruction of Jewish life by the Nazi regime. Only a single mention in Freundlich’s memoir helps reconstruct the home as a space where her political consciousness was sharpened by family, friends, and colleagues.45 Until today, most of Freundlich’s photographs remain lost, and hundreds of unsorted documents in her archive are essentially inaccessible.46 In one of the few commentaries on Freundlich’s life and work, German scholar Jacqueline Vansant notes that Freundlich’s home belonged to a topography of places that affirmed the “spatial, temporal, and social coordinates of [her] early life” and reflected the ways in which Jewish Austrians affirmed “the ‘we’s into which they were born” in Vienna.47 Freundlich’s postwar writing focused on forms of erasure and the competing histories of expatriates and exiles, Communists and Social Democrats, as well as Jewish and non-Jewish dissidents among these resistance groups. She also dedicated her life to writing about the differences they confronted in the face of a pervasive culture of forgetting in Austria, in which national and political affiliations remained central, displacing notions of religious and cultural identity. |

2. In Motion, 1939–1940

Who moves us, makes us experienced

Who pushes us far, pushes us wide.

Now we owe everything to years in motion,

And not those of our childhood.

—Günther Anders, cited as an epigraph in Elisabeth Freundlich’s memoir The Traveling Years

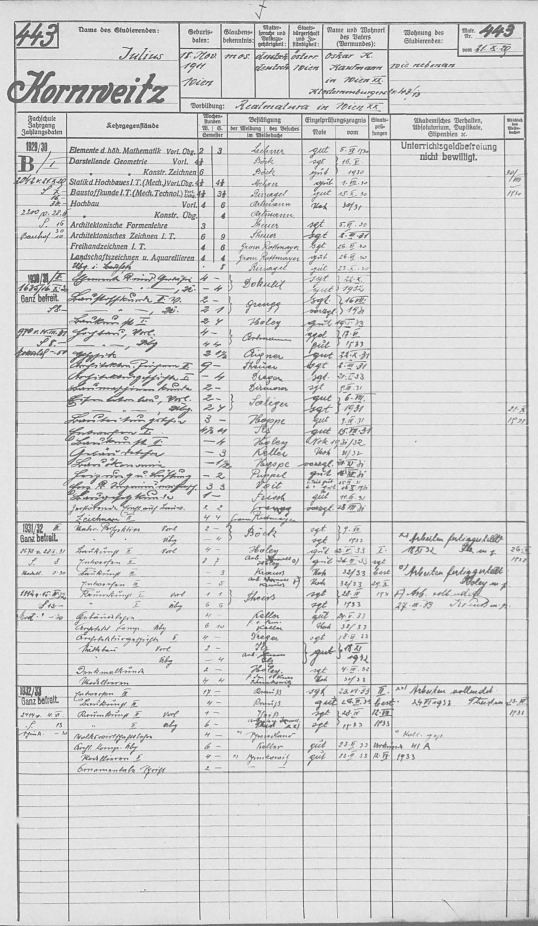

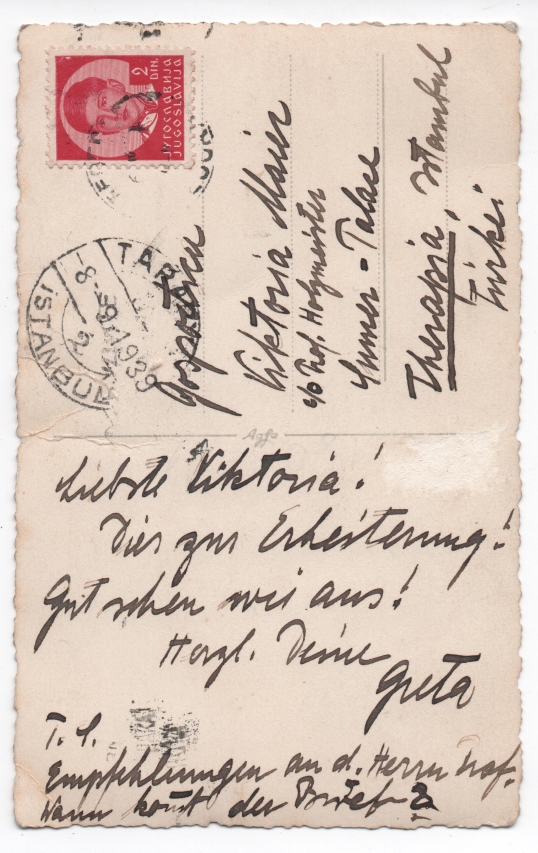

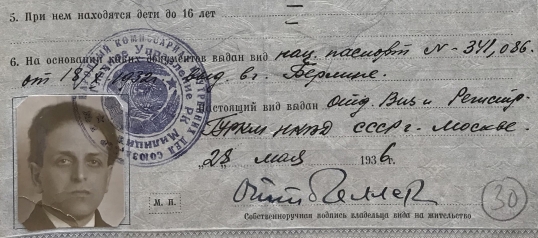

Julius Kornweitz, Franz Öhler, and Greta Vajs Aleksić, or Safe Houses in Zagreb and BelgradeOnce they departed on missions, those who worked in the resistance experienced periods of grave danger and constant instability. Schütte-Lihotzky left Istanbul in December of 1940 to carry out active resistance in Vienna as a member of the Communist Party. Eichholzer and Maier Mayer advanced on separate missions earlier in the same year. Procuring spaces for secret meetings remained a constant struggle as resistance fighters traveled through foreign cities. As middlemen and party figures provided further instructions and secret addresses for final destinations, a stable network of safe houses in metropolitan areas was key. Just like in Istanbul, these regular meeting places were located in private residences, but they relied on the hospitality of acquaintances, friends, and family. Maier Mayer, for example, stayed with her friend and colleague, the architect Greta Vajs Aleksić (1913–after 1956) in Belgrade, who had also studied with Holzmeister in Vienna. With her husband, Dragan Aleksić (1901–1958), she was involved in the Yugoslav resistance.48 While some who provided refuge and safe houses were active resistance fighters in their own countries, others were unaffiliated with the Communist Party, or any party at all. Access to safe houses, in particular, required more than solidarity along party lines and often relied on old friendships and people who supported resistance activities materially. For example, in Zagreb en route to Austria on her mission, Schütte-Lihotzky and Maier Mayer met Julius Kornweitz (1911–1944) at a safe house that was the residence of Franz Öhler (1887–1945), whom Eichholzer knew from Graz, his home city. Öhler had fled to Zagreb after being exiled in the aftermath of the “Anschluss.”49 In Yugoslavia, he financially supported most of Kornweitz’s missions between 1938 and 1940, despite the fact that he was not affiliated with the Communist Party.50 Kornweitz was the technical director of the Communist Party of Austria in charge of foreign operations. Professionally, he was trained as an architect. According to historian Hans Schafranek his skills included the “forging of passports, making chemical ink for letter writing, as well as the preparation of books in which party directives and money were hidden, furthermore the drafting of political letters.”51 In the context of the Austrian resistance, he was in regular contact with the Central Committee of the Communist Party in Moscow and headed and coordinated communications between multiple dissident groups in Sweden, Switzerland, Slovakia, Turkey, and Hungary.52 Given that Kornweitz was Jewish, his position directing dangerous international missions while traveling across borders was particularly precarious. Fig. 6. Julius Kornweitz’s University Transcript, Vienna, September 10, 1929. Technical University, Vienna. Instructions in safe houses were utilized to exchange materials, money, and agitprop but they also implied familiarizing people with resistance strategies, which could be both textual and corporeal. Meetings with Kornweitz acquainted many resistance fighters with practices of encryption. He taught Maier Mayer to decode secret messages through a sequence of fractions. In this system, numerators and denominators indicated lines and letters on the page of a book that served as a prearranged key. Schütte-Lihotzky, too, received instructions from Kornweitz in Zagreb.53 He gave her a message containing the names and addresses of contacts in Vienna, encrypted according to the same system. The note provided the only key to accessing resistance networks and clandestine geographies. Schütte-Lihotzky arrived in Vienna on December 30, 1940, having hid the message in her ear canal.54 Fig. 7. Picture Postcard from Greta Vajs Aleksic (left) to Victoria Maier Mayer (right), photo taken in Belgrade, 1939. Personal Archives of Carla Gonzalez Maier. Fig. 8. Picture Postcard from Greta Vajs Aleksic to Victoria Maier Mayer, 1939. Personal Archives of Carla Gonzalez Maier. Despite Schütte-Lihotzky’s postwar effort to write the people she met along routes of resistance into evidence, few records of their lives and contributions exist today. For instance, although Öhler’s family was prominent in Austrian society, having owned a department store chain in Graz and Vienna, information about his life is scarce. Only one university transcript survives as a record of Kornweitz’s architectural career (fig. 6). Vajs Aleksić’s political and artistic accomplishments remain entirely obscure—marking the persistent silencing at the intersecting lines of religion and gender.55 She was forced to flee Austria in 1935 because of her Jewish identity. A photograph shows her with Maier Mayer on a busy street in Belgrade in 1939 (fig. 7). The women look hurried, and the image seems to have been captured in haste. Taken a year before their dangerous 1940 reunion in the same city, it suggests that the two friends may already have been involved in resistance activity. “[Sending] this for [your] amusement! We look well!”56 Vajs Aleksić wrote to Maier Mayer on the back of the photograph (fig. 8). “Recommendations to the Professor [Holzmeister]! When will the letter arrive?”57 It is impossible to say if the letter Vajs Aleksić refers to was related to resistance activity. Historians have remarked on the complexity of finding definitive personal commentary of resistance activity, which, by nature, had to remain strictly clandestine. Yet, the photograph is one of the few pieces of evidence documenting the friendship of two female dissidents. Gestapo files amassed in interrogations, often under torture, contain names and activities, but such records are the products of persecution. In contrast, faded photographs and academic transcripts are records of dissidents’ collective and individual creativity, achievement, and defiance in the face of immense danger. They reflect a world characterized by danger, terror, and systematic persecution. Yet, they also impart a view of resistance and exile from the lived experience of dissenters in the attempt to reclaim a sense of agency in that world.58 |

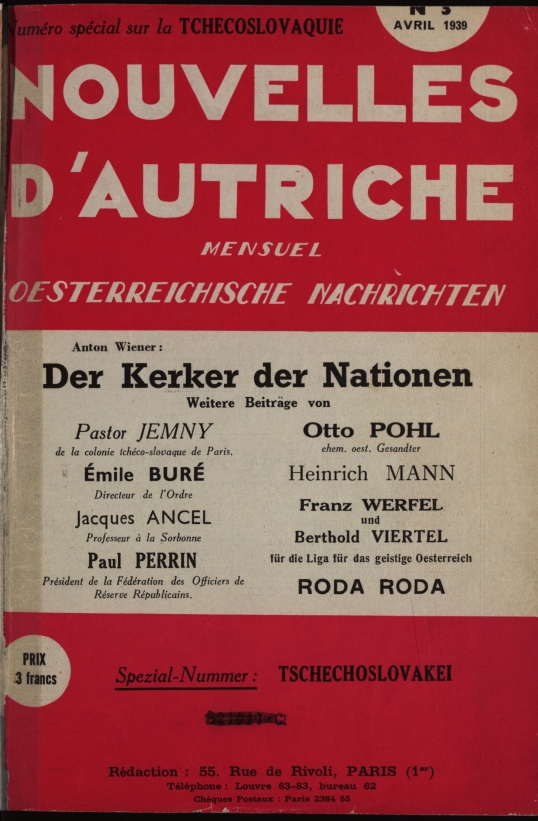

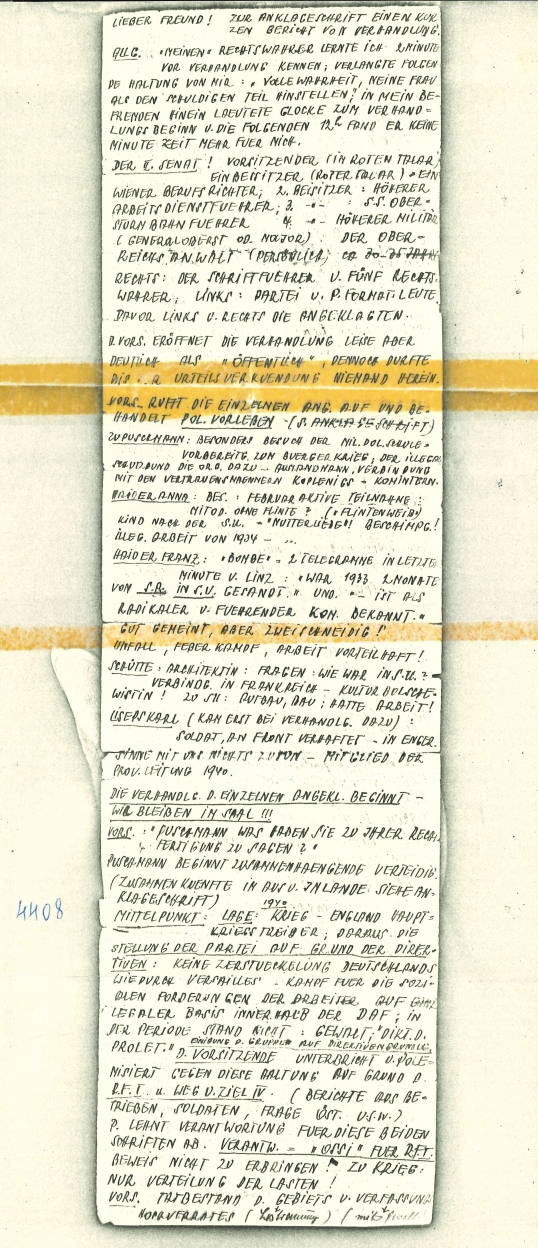

Erwin Zucker-Schilling, Elisabeth Freundlich, and Otto Heller’s Editorial Office in ParisWhile relying on the individual body was central to the labor of resistance, building strong fellowship and community was equally important. Freundlich developed critical relationships upon joining the editorial team of the French- and German-language monthly publication Nouvelles d’Autriche in Paris in 1939. The editorial mission of the journal, which was supported by the Communist Party of Austria, was to provide unbiased news from and about Austria for people living in exile in France.59 Drawing on her background in theater and cultural criticism, Freundlich promoted events, reviewed books, and developed cultural programming. The editorial office operated in the center of Paris, first from rue de l’Ancienne-Comédie 13, in the sixth arrondissement, and then from rue de Rivoli 55, in the first arrondissement.60 The journal was published for only a few months, from spring until winter 1939, and its editors escaped Paris in June of 1940 when the “Wehrmacht,” the Nazis’ armed forces, occupied the city. For this brief period, the editors solicited literary and artistic commentary from dozens of international writers and intellectuals in Paris, including Heinrich Mann (1871–1950), Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps (1864–1945), Franz Werfel (1890–1945), and Roda Roda (1872–1945). From its inception, Nouvelles d’Autriche was established with the broad mandate to support the politics of the Front populaire, or popular front.61 It aimed to represent non-partisan views, drawing on contributions from Communist, Christian Social, and even monarchist authors. Devoted Social Democrats, many of whom had joined the ranks of Revolutionary Socialists in exile, were less involved in Nouvelles d’Autriche’s publishing ventures. They had established their own publication in exile in France and they also fundamentally disagreed with the politics of the popular front. In their view, sharing a cause with conservative groups weakened the anti-fascist objective.62 Moreover, Revolutionary Socialists opposed the Communists’ stance on the “national question” and believed that the “resurrection of an independent Austria” was shortsighted and could only be realized if all German and Austrian workers were united in their fight against National Socialism.63 Supporting the communist position on the matter, Austrian politician Otto Leichter (1897–1973) at the time wrote to the contrary that the Austrian working class should not chain its fate to Germany’s.64 Fig. 9. Cover of Nouvelles d’Autriche, Paris, April, 1939. Austrian National Library. Despite her upbringing in a Social Democratic family, Freundlich summarized her political decision to join Nouvelles d’Autriche’s editorial team by stating, “I myself belonged to no party, but the call of the hour seemed to me to be the bringing together of all those who had made the fight against barbarism the primary goal of their lives.”65 She was, indeed, not formally affiliated with any party, but believed that alliances, especially between left-leaning groups, were crucial to anti-fascist resistance struggles in Austria and elsewhere.66 Nouvelles d’Autriche offered a forum and, in its editorial offices, a space to work towards this goal and to cope with the experience of exile through mutual aid, bilingual communication, and cultural exchange. The strict hierarchy of the Communist Party of Austria, which operated from Paris until 1938 and then from Moscow, insisted that one of the party’s functionaries maintain the position of editor for Nouvelles d’Autriche. Erwin Zucker-Schilling (1903–1985) was initially tasked with the endeavor, since he was a prolific journalist who had been coopted into the party’s central committee.67 However, informally the Jewish Czech-Austrian-German writer, political activist, and economist Otto Heller (1897–1945) served in the role of editor-in-chief (fig. 9).68 Heller was fluent in French, had substantial experience heading Communist newspapers and radio stations, and had published a number of multilingual books. The Communist Party of Austria regarded these qualifications as imperative for the success of Nouvelles d’Autriche.69 The editor-in-chief had to be able to address an audience of German and French speakers while drawing on subtle cultural and linguistic idiosyncrasies. Incubating a discussion about cultural life in exile, moreover, was central to the goals of the popular front. Historians Kristina Schewig-Pfoser and Ernst Schwager note that “in cultural matters emigrants in France were largely left to their own devices.”70 Between 1938 and 1940 cultural and artistic life of émigrés in France was not “as rich and versatile” when compared with North America, according to Schewig-Pfoser and Schwager. Yet, for a period of time, Nouvelles d’Autriche had a role in filling this void.71 Acknowledging readers’ heightened precarity, Nouvelles d’Autriche’s editorial team focused on topics related to the idea of belonging—artistically, culturally, communally, and spatially. Editors dedicated substantial space in the publication to assert the party goal of reestablishing Austria’s independence while at the same time outlining multifaceted approaches to cultural resistance. The question of Austria’s autonomy was important for citizens of Jewish descent, some of whom registered in Paris as “ex-Autrichennes,” which was a symbol of protest, a rejection and reframing of the right to country after the “Anschluss.”72 The journal encapsulated this condition of belonging in between but also advocated for the sovereignty of a country that no longer was. It wore this position on its cover, which was designed to resemble the Austrian flag that had ceased to exist in 1938. Editors used bilingual cues to stake their position and speak to the readership of exiles. The mention of Austria in the journal’s title defied the Nazis’ erasure of Austria’s separate political existence, yet it rendered the name in French. It therefore asserted that only from the perspective of a language and a country in which freedom of the press remained intact could one conceive of Austria. Numerous articles drew on the audience’s familiarity with the Austrian dialect and made puns in German and French. These nuanced visual and linguistic valences were likely envisioned by Heller, who had a profound sense for translation and transliteration. In the offices of Nouvelles d’Autriche, editors undertook substantial community-building efforts through artistic programming and legal aid together with the Cercle culturel autrichien. The circle held daily office hours and provided advice about questions of emigration.73 Nouvelles d’Autriche advertised the circle’s concerts, lectures, and day trips, which were ways to build connections among refugees. Freundlich gave lectures on the history of literature and moderated discussions.74 Practical services such as guidance on how to access libraries in Paris were crucial for thousands of people trying to establish lives in a new city or to locate friends and family. Building community and providing resources to those in exile after and amid dire conditions of surveillance and capture demonstrated techniques of cultural resistance. Such spatial practices of dissidence revealed a dialectic in which friendships animated spaces for care and in which space became operational in building networks for mutual aid. Under Heller’s leadership, Nouvelles d’Autriche was envisioned as an exilic space, a place of being in-between. Despite his life-long dedication to the Communist Party, Heller had confronted complex questions about multiple modes of belonging, at times cruelly, himself. Exiled three times between 1933 and 1938, he had been stripped of his Czech, Austrian, and German citizenships, one by one. His only legal document in France was a carte d’identité.75 The work for numerous communist publications and newspapers notwithstanding, his role in the party and his family’s life in exile always remained tenuous. Papers from his time in the Soviet Union between 1934 and 1937, for example, confirm that Heller was described by other party members as “unreliable” due to his writings on Judaism, anathema in Marxist doctrine. In 1937, he only narrowly escaped the Stalinist purges (fig. 10).76 Even in the postwar years, as archival documents of Heller’s life became available, Austrian literary scholars attributed the editorship of Nouvelles d’Autriche to Erwin Zucker-Schilling, constituting a double erasure of Heller’s achievements. Fig. 10. Otto Heller, Official “Resident Permit for a Foreigner” in the USSR, Moscow, 1936. Russian State Archives, Moscow. It is difficult to precisely reconstruct the editorial offices of Nouvelles d’Autriche today, but Freundlich captured its atmosphere in a 1991 memoir. She describes it as an environment of care and learning in spite of the odds, where multiple languages were spoken and where people made new connections and friendships beyond strict party lines. Events of various scales, including trips, concerts, and poetry readings, allowed people to forge relationships and celebrate artistic accomplishments such as the publication of new books. The journal featured literary commentaries that persistently covered and decried the crimes of the Nazi regime. In the editorial process, Heller “never permitted any linguistic sloppiness” and insisted on “tracing the social and historical roots of every event,” Freundlich remembered.77 He argued that words, language, and speech were critical resistance methods and expressed the need to be wary of empty political catchphrases. His attention to belonging in thought and multiple forms of translation was emblematic of the concepts and the spaces built and imagined by Nouvelles d’Autriche. |

3. Cities, 1940

From Hamburgerstraße,

To Holzknechtstraße

Then Schönbrunn

Rue de Rivoli

And Salle Adyar

Are not Westbourne Terrace 124

A Settler’s House and a Public Park in ViennaDeep familiarity with cities for the purposes of arranging carrier services and secret meetings with emissaries was a precondition for resistance labor. Specific knowledge about the urban geography of districts and less-traveled neighborhoods helped operatives evade surveillance, or at least it was assumed that it did. When Schütte-Lihotzky and Maier Mayer arrived in Vienna from Istanbul in 1940, they put the strategies they had rehearsed in domestic contexts into practice, in neighborhoods they were intimately familiar with. Schütte-Lihotzky stayed at her sister’s house and went to meetings only after taking meandering walks through the city. Amid the unrelenting danger of being discovered, dissidents relied on their close experience with the urban physical and social fabric to ensure that they were not being followed. In what would become twenty-five days of active resistance in Austria, Schütte-Lihotzky drew on her knowledge of urban demographics, transportation systems, and Vienna’s daily rhythms. She crisscrossed narrow alleyways in the Innere Stadt and took the tram to the Vororte, the outskirts. By traversing the Ringstraße’s wide, open boulevards in the late morning and early afternoon hours, when she knew few people would be out, she exploited Vienna’s infrastructure for insurgent objectives. One afternoon, Schütte-Lihotzky took long detours through the park at Schönbrunn, the former imperial residence (fig. 11), when she believed she was being followed.78 The axial plan and wide avenues of the Baroque landscape made it possible for her to conclude there was no one in sight. The park’s monumentality and its imperial architecture were mobilized against the totalitarian state through embodied resistance. Fig. 11. View towards Gloriette at Schönbrunn grounds, Viennna, 1935. Austrian National Library. Sp. 202. Schütte-Lihotzky’s initial success in navigating the city emboldened her to accomplish her primary and secondary missions in Vienna: to read and memorize anti-fascist literature for reproduction and dissemination abroad and to persuade the head of the communist resistance in Vienna, Erwin Puschmann (1905–1943), to leave the country because of fears that the organization had been compromised. To this end, she studied leaflets and agitprop for two afternoons in a small house, in the working-class district of Favoriten.79 The social fabric of the city in this mission played a critical role, since working-class areas—many of them close to factories—were the last strongholds of organized resistance in Austria. In Favoriten, Schütte-Lihotzky was able to make connections with a group of resistance fighters grouped around the typesetter Anton Konopicky (1889–1945). Together with his wife, Therese Konopicky (1889–1943), he had enabled the reproduction of anti-fascist leaflets. In their home at Holzknechtgasse 103, Puschmann often found a temporary hideout and meeting place. Schütte-Lihotzky met with Puschmann multiple times at this location and in coffee houses, which they incorrectly regarded as sufficiently anonymous for concealing their encounters. The day before Schütte-Lihotzky’s scheduled departure for Istanbul, Maier Mayer was to meet her at her sister’s apartment on Hamburgerstrasse, likely to hand off contacts and addresses of safe houses in Vienna and abroad. On this afternoon, January 22, 1941, the Gestapo captured Schütte-Lihotzky and Puschmann during their last secret meeting. In the waves of arrests that followed, the Gestapo searched numerous apartments and detained hundreds of resistance fighters. When Maier Mayer arrived at Schütte-Lihotzky’s sister’s residence that afternoon, she too was seized by the Gestapo. In the darkest hours of the months of terror, pain, and trepidation that followed, Schütte-Lihotzky and Maier Mayer recalled that they imagined urban and rural landscapes they had visited.80 By withdrawing into memory, they attempted to think beyond the reality of constant fear, terror, and violent subjugation. Practices of resistance—from actual ambulatory circuits to imagined landscapes—exemplified critical spatial and temporal characteristics of dissident labor and coping mechanisms under duress. “Yesterday I dreamt that I was walking with you on a beautiful path of fresh green grass, to the left, a row of beautiful flowering bushes,” wrote Schütte-Lihotzky to her husband in a rare censored correspondence months later from the Gestapo prison in Vienna.81 “I said to you that I had such a difficult period behind me that I thought I would never see something beautiful with you again. I cried when I awoke, but as always, I swallowed my tears right away because I’m thinking of my health!” Such methods of coping with immense trauma elude conventional archives of architecture, but they permeate letters, testimony, recollections, and memoirs. |

|

4. Spatial Practice, 1941–1945

They will wander until the end of my life in front of my inner eye.

The shadows silent one after the other.

—Richard Zach, poem smuggled out of the Schiffamtsgasse prison on a kite, Vienna

Textiles, Terms, and Infrastructure at SchiffamtsgasseWhile resistance activity in the city meant applying one’s bodily and mental faculties, once captured, the terror of interrogation, torture, and killing at Gestapo prisons necessitated emotional assistance from others, especially when each person was kept in strict solitary confinement. Some dissidents tried to complete introspective work to maintain dignity and the possibility for creative expression.92 When possible, most sought to continue communication with the outside world and to strengthen bonds with those in nearby cells. Establishing such contact was challenging given the strict observation and the severe punishments by the Gestapo to which people were constantly subjected. In Vienna, captured resistance fighters were transported to interrogations multiple times at the Gestapo headquarters in the former Hotel Métropole. During these interrogations they were tortured with “threats, insults, standing for hours, water and food deprivation, slaps, punches, kicks in the abdomen, beatings with rubber truncheons, whips, pizzles, and steel rods … burning cigarettes, shackling with chains, and the hanging of bound victims from doorframes.”93 Schütte-Lihotzky describes the Gestapo’s sadism, writing that they castrated Puschmann, the highest-ranking member of the Austrian communist resistance, before he was executed by the Nazis in Vienna in July 1943. On April 22, 1941, three months after their arrest, Schütte-Lihotzky and Maier Mayer were transferred to Vienna’s former district prison at Schiffamtsgasse, where the Gestapo incarcerated resistance fighters for months in solitary confinement. Their meeting in a van on the way to prison was the first time the two women had seen each other since their Istanbul meetings a year earlier. In those few minutes, they spoke briefly and quietly, agreeing on the points they would adhere to in the sham trials that awaited them.94 This moment of familiarity and unity strengthened their continued belief in the necessity to fight back. The psychological strain on all women interned with Schütte-Lihotzky and Maier Mayer on the fourth floor of Schiffamtsgasse was tremendous. Stemming mostly from working class backgrounds, they lived in constant fear of their own execution or that of their partners, who had often also worked in the resistance. Schütte was relatively safe in Turkey, but Eichholzer had been captured shortly after Maier Mayer in Austria. As Schütte-Lihotzky awaited an almost certain death sentence, dirt, cold, and malnutrition ravaged her body; she suffered an outbreak of scabies and ceased menstruating.95 Maier Mayer was in grave danger because she held a central role in establishing communication among resistance groups both within and beyond Austria and had collaborated with multiple people for over a year. What gave both Schütte-Lihotzky and Maier Mayer strength in these conditions, was that many other women imprisoned at Schiffamtsgasse shared their goals and some had been acquainted from resistance work before their capture. These bonds enabled them to develop techniques of information exchange within and beyond prison walls. Inside, the imprisoned resistance operatives communicated covertly to strategize their statements and avoid revealing information.96 For instance, those who could establish visual connections communicated between cells with a simple system of hand signs. Others used a basic Morse code. A knocking signal became a warning of guards’ imminent arrival. Another method of disseminating information was the production of Kassiber, or kites, secret messages written on paper or cloth (fig. 13). Dense printed texts were concealed in the seams of clothing or building cavities and transported at great risk within the prison and to the outside world. Architectural critics Ines and Eyal Weizman have theorized the practice of writing in cells as “acquiring a potential subversive content, becoming critical spatial apparatuses” to foster “the individual’s impulse to survive through texts, through reclaiming her own voice against the imposition of others, creating an autarkic realm in which practices of dissidence, political and personal, could be reinstated.”97 I acknowledge this critical framework but note that writing in this case primarily served practical functions of exchange and the building of solidarity. Fig. 13. Kite from Gestapo prison at Schiffamtsgasse, Vienna, 1942. Documentary Archives of Austrian Resistance, No. 440. In addition to exchanging information, resistance fighters developed the method of Schnürln, or fishing, to extend care and sustenance. This was a way to aid fellow inmates whom the Gestapo had brutally abused in basement cells and who had gone days without food. Woolen threads were strung out of prison windows to send kites with information or nourishment down to the basement. Resistance fighters in vertically aligned cells added a portion of their meager daily rations to the kite and lowered it to the person in need. Plumbing provided another critical infrastructure to detained resistance fighters in Schiffamtsgasse. Connecting a total of almost thirty cells across four floors, toilet ducts were a means of communicating with other prisoners in the levels below. As speech amplifiers, they were essential in transmitting warnings and advice and in exchanging stories about the continued struggle, about hope, and about a life that once was and that could once again be. Over the months of internment, this system allowed prisoners to deliver lectures and in one instance even to become part of a celebration. “We celebrated May 1, 1942, twelve men and eight women, all Communists, over the toilet,” Schütte-Lihotzky recalled.98 Hedwig Urach (1910–1943), who had been a key organizer in Vienna factories, delivered a festive speech, according to Schütte-Lihotzky, that focused on resolution and uplift. Urach’s continued defiance and her friendship, which developed through the wall between their cells, gave Schütte-Lihotzky hope. These methods of building collectivity in isolation were supported by precious, precarious leisure activities. Schütte-Lihotzky took part in crafting intricate spatial puzzles and crosswords that could mitigate the constant sense of hopelessness with terms that only the interned comrades were familiar with. A crossword contained resistance fighters’ “prison names”—different from the pseudonyms they had used in freedom—and disparaging nicknames the women had assigned to their guards. It reflected the necessity of disassociating oneself from the reality of terror while actively confronting it. Though distinct from the introspective production of texts that Ines and Eyal Weizman theorize, these crosswords were nonetheless forms of subversive, clandestine co-writing. Fig. 14. Miniature Slippers, Vienna, ca. 1942. AzW, Architekturzentrum Wien, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky Gefängnisbuch, no. 405. Covert craftsmanship also served as a form of subversion of practices of forced labor. For example, Schütte-Lihotzky secretly crafted a nightstand from cardboard boxes containing effervescent tablets, which detainees were forced to wrap. The design of the nightstand is lost, but it was likely foldable so as to be flattened and hidden under a blanket or a straw sack. In the 1920s, Schütte-Lihotzky had devised dozens of foldable household objects, including pull-down beds, folding chairs, and portable tables. Seen in the context of her design practice, the nightstand served as a reminder of the possibility of freedom and social space. In solitary confinement, Maier Mayer spent days untangling a ball of wool and then sorting each thread by color and size. When a guard gave her a large package of stamps, she classified them and—as she recalled decades later—lived in “the small worlds” of each of their pictures.99 Most women at Schiffamtsgasse were forced to cut fabric remnants that were then woven into rag rugs. While some of these tasks required creativity, they were done under coercion and women were often abused by the guards. Yet, on several occasions, the prisoners—many of them trained as laundresses, seamstresses, and weavers—hid threads from the fabric and crafted presents for one another. These textiles became signs of solidarity and turned the labor power that had been stripped from them into acts of care and resistance. “Miniature note-books with good wishes” and “slippers, as a symbol of one day ‘walking to freedom’” were the products of care and suffering that Schütte-Lihotzky remembered (fig. 14).100 |

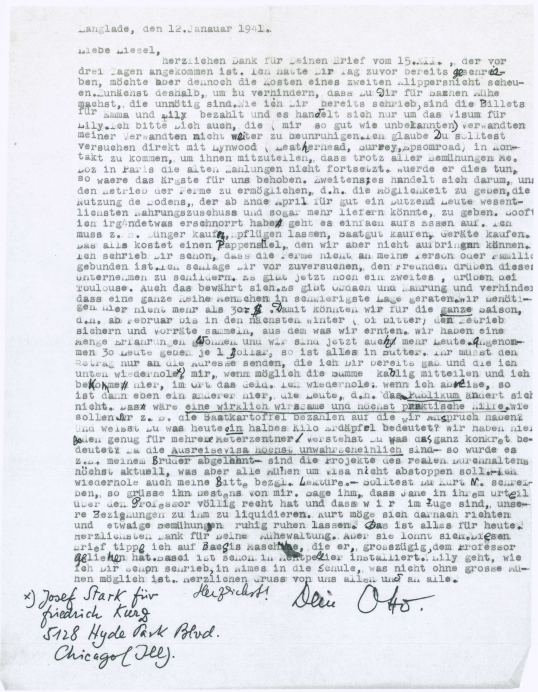

A Typewriter, a Library, and a Farm in LangladeIn the fall of 1940, the editorial staff of Nouvelles d’Autriche were forced to flee Paris. The occupation by the “Wehrmacht” and the establishment of the authoritarian Vichy government spelled the end of what was considered safety in France. Many of those fleeing Paris sought refuge in the south of the country, in the “zone libre,” which was strictly controlled by the Vichy regime. From there, thousands of people hoped to secure passage to Spain, Portugal, and beyond. But the movement of foreigners in France had already been restricted considerably.101 To protect their staff and readers, editors at Nouvelles d’Autriche began to destroy documents and membership records in 1939, before Heller, Freundlich, and Zucker-Schilling had to abandon the offices. Freundlich and her aging parents hid in Montauban, in the South of France, and then made a grueling walk over the border into Spain. They reached Portugal after traversing the Pyrenees on foot in the fall of 1940.102 With valid emergency visas, they embarked on ship from Lisbon bound for the United States, which reached safe harbor in New York in November. In this new city, the family lived first in a hotel, where Freundlich wrote countless letters to friends, and sought to assist others by knocking on the doors of refugee organizations. For Jewish people living in France after 1940, establishing communication with family members and refugee organizations was of the utmost importance. Secure hiding places were scarce and difficulty in locating them was compounded by continual forced displacements and denunciations. Many emigrants living in France, suspected of being foreign spies, had already been displaced or temporarily held in internment camps. Together with more than two thousand men registered as “ex-Autrichiens,” Otto Heller was forced to report to Paris’s Stade Colombes in September of 1939. From Colombes the men were deported to the Meslay-du-Maine internment camp. Conditions at Colombes and Meslay-du-Maine were dire. A friend remembered that Heller knew “through the art of narration to keep the morale high, which was severely compromised due to the horrendous quarters—50 cm beds of straw for each.”103 In January 1940, Heller was briefly released, but interned again in May. He was then required to labor in the “Compagnies de travailleurs étrangers.”104 The companies were made up of foreigners, many of them young brigadiers who had fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War. They were tasked with completing infrastructural developments in the service of France. While in the companies in the south of France, Heller negotiated a temporary release on the condition that he would spearhead agricultural work at a farm in the village of Langlade, in the Vaunage.105 Only months later, thousands of people from the companies were systematically deported to concentration and exterminations camps in Germany, Austria, and Poland. Scant records of life at the farm reveal details about sociability and aid work that has previously eluded historians. In 1940, Heller had located an abandoned agricultural building, which in letters to friends he lovingly referred to as his ferme. The plan was to make the farm arable and to create a new space of refuge for exiles in France. Reunited after a year apart with his wife Emma and their daughter Lily, Heller sheltered up to thirty brigadiers from the companies at the farm. He anticipated making the farm self-reliant, by planting and growing vegetables. In addition, Heller set his mind on political education. In a correspondence that continued for a few months between 1940 and 1941, he instructed Freundlich to send books from New York. The farm was not to be a liminal place of existence but one with communal spaces, including a library.106 Despite the fact that food grew scarcer by the day, a communal meal for at least a dozen people was prepared every evening. Heller was able to obtain a typewriter from a colleague for a few days, an acquisition that inspired him to continue journalistic work. The farm became an example to others, and Heller was in contact with at least one other stronghold modeled after the Langlade community.107 Despite such small triumphs, life continued to be extremely precarious. Fig. 15. Letter from Otto Heller to Elisabeth Freundlich, Langlade, January 12, 1941. Deutsches Literatur Archiv, Marbach, Papers Elisabeth Freundlich. Conditions at the farm deteriorated over the winter of 1941. In a January 7 letter to Freundlich (fig. 15), Heller explained their perilous situation: It is bitterly cold, down to -10° with snow, which has not been observed in these environs in living memory. At least in two rooms, it is warm in here, but there is neither electricity nor a bathroom (look around in your hotel room in New York)… . Dozens have stayed with us already, at Christmas we were 15, New Year’s 12, this is a true refuge.108 A week later he wrote again with more urgency, hoping for aid and assistance in the procurement of visas: Whenever I have been able to scrounge something together, it is just used up instantaneously for food. I already wrote that the whole undertaking [at the farm] is not tied to my person or my family. It provides shelter and food and it prevents a lot of people from slipping into the most difficult circumstances… . Do you know what half a kilo of earth means for us today? Since our emigration visas are highly unlikely to arrive—my brother’s visa, for example, was denied—projects of real perseverance are highly relevant, but this should not stop [you from] any efforts to continue to attempt to secure visas [in New York].109 Freundlich wrote dozens of letters to relatives and worked with refugee organizations tirelessly from New York. Her efforts focused on obtaining a visa for Lily Heller and on sending money and food to Langlade through refugee committees. Although she did not know it until after the war, the foodstuffs successfully reached Heller’s family and made it possible for Lily to attend school in Nîmes.110 In his last letter to Freundlich, dated March 15, 1941, Heller describes the difficulties he faced in emigrating, despite having obtained Mexican visas for himself and his wife. Lily was still without a visa, and Heller’s statelessness meant that he could not cross into Spain. He wrote: We are blessed with ship tickets now, unfortunately not with milk for Emma, who was sick for two weeks, and who needed it urgently… . Now I have two vouchers and I will use it to telegraph in god’s name (instead of buying something to eat). Now what? … . We have deep roots here and the soil is firm but in motion. We can’t get away… . Could you send Emma milk somehow? Dry milk or condensed milk! It is urgent because Emma is seriously ill … Greet all friends and acquaintances from me, from us. It is very possible that we will see each other again very soon. Either way, here or there. Here everything is blooming and the owls are singing at night. Everything is somewhat peculiar. But that’s probably the story of our generation.111 In the spring of 1941, following denunciations from within the ranks of sheltered political exiles at the farm, Heller and his family were apprehended.112 Heller faced a sham trial for “illegal activities” at the farm and was imprisoned. In 1943 he was able to flee north and join the French Resistance inside a “Wehrmacht” unit. In the same year, however, his activities under his alias Raymond Brunet were discovered and he was deported to the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp. Emma Heller and Lily Heller were captured and deported to Ravensbrück, the largest concentration camp for women in Nazi Germany.113 Little can be pieced together of the Hellers’ life after deportation. Secondary sources indicate that Otto became part of the international resistance group, Kampfgruppe Auschwitz, which organized the smuggling of news out of the extermination camp.114 The group was also responsible for transporting the first photographs documenting Holocaust atrocities in Auschwitz to the outside world, which Georges Didi-Huberman theorizes as “images in spite of all.”115 Considering the conditions in Auschwitz it is problematic to think of stable roles within the Kampfgruppe. Survivor testimony and secondary literature suggest that for a period Heller seems to have been involved in gathering testimony from other victims in Auschwitz to be transmitted to a Polish resistance group in Krakow. With its help, at least one source asserts that these testimonies were published as the information bulletin Auschwitzer Echo and eventually broadcast on British radio.116 In 1945, Heller was part of the death march from Auschwitz. Of the sixty thousand people forced to make the grueling walk on foot in the bitter cold to the city of Wodzislaw, fifteen thousand were killed. From there, Heller was then deported to Mauthausen and then to the sub-camp Ebensee.117 One hundred kilometers from his birthplace in Vienna, he died on March 26, 1945. The formal report from the concentration camp’s “infirmary” states his cause of death as infection, which was often the false cause given for severe starvation.118 Emma and Lilly Heller were liberated at Ravensbrück in 1945.119 Freundlich remained in exile in New York until the late 1940s. In 1943, she enrolled in library sciences at Columbia University, which she concluded was the only way to attain a degree quickly and find work.120 The education enabled her to find temporary employment at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and as an adjunct professor at Princeton University.121 However, her most prized work was editing the cultural supplement of the exile publication The Austro-American Tribune (see cover image). Published in German and English, the Tribune united exiled writers in New York and across the United States, some of whom Freundlich had met in Paris at Nouvelles d’Autriche, including Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956). As editor-in-chief of the cultural supplement, she was instrumental in building a community around the publication by hosting gatherings in Columbia’s Morningside Heights neighborhood. She wrote about theater, literature, and architecture and how they reflected the experience of exile, loss, displacement, and mourning during and after the Holocaust. In a 1946 contribution to the journal, Freundlich published the first public obituary of Herbert Eichholzer, an architect who she had met in Paris in 1938 at the Ligue de l’Autriche vivante. It is likely that Heller had tasked Eichholzer with founding a clandestine resistance cell consisting of architects Schütte-Lihotzky, Schütte, Maier Mayer, and a few others in Turkey.122 Although the two groups’ resistance strategies articulated distinct views on identity and belonging, one nationalist and the other exilic, they felt committed to each other, their friendships, and the inalienable necessity to resist. |

Archives, Historiographies, and Kinship

The period between 1933 and 1945 has been a focus of architectural history for five decades.123 However, those who resisted Nazism, especially in the conditions of exile, imprisonment, and internment, have rarely been considered in architectural history.124 In part this absence is due to the instability of archives as well as the methods typically employed in architectural history and theory, which rely on visuals—plans, diagrams, illustrations, and photographs—as well as material artifacts for scholarly work. Survivor testimony, primary sources, such as letters and even novels, and materials artifacts have at times eluded architectural scholars in the writing of history.

Throughout this essay, I have attempted to elucidate a history that relies on victim and survivor testimony and that does not predominantly focus on the records amassed by the Nazi perpetrators. Instead, by concentrating on how practices of dissidence were articulated in artifacts, infrastructure, cities, and landscapes, I have attempted to chart a variety of cultural forms of resistance at the intersection of dissident lives and how they occupied and animated space in oppositional work. Due to the lack of visual evidence of these forms of resistance, I have rendered texts and objects spatial. Ordinary spaces—guest quarters, apartments, safe houses, editorial offices, a public park, and a farm—were critical sites where resistance fighters devised and enacted forms of belonging in the face of totalitarianism. In a discipline that has predominantly confirmed narratives of oppression rather than offering histories of resistance to them, this method is meant to chart one version of an alternative archival approach. The archive’s presence in this essay affirms how a figuration of seemingly lost spaces and artifacts can illuminate spatial histories of dissidence, as well as competing legacies of historiography and memory in Europe. In conclusion, I therefore add the archive to previous discussions of domestic and public spaces, because it is where distinct visions of resistance and exile continue to become articulated in ways that shape our present.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Elisabeth Freundlich both published memoirs of the time between 1938 and 1945. Their books were among the first written by female Austrian authors to tackle the experience of resistance and exile.125 Their memoirs both trace people and friendships and show their opposition to and suffering under the Nazi regime. While Schütte-Lihotzky’s memoir takes up questions of class, gender, and international anti-fascist resistance, Freundlich’s works against hegemonic histories of the nation and party and introduces identity, religion, culture, and notions of Jewish achievement and belonging as central categories of understanding difference.126 In writing about friendship and loss, Schütte-Lihotzky and Freundlich produced archives using drawing and creative writing, respectively—mediums with which they were intimately familiar. Their texts contain recollections of people but also critiques of the contemporary conditions of memorialization from which they emerged. As such, they are collections of memories but also revisionist histories.

Schütte-Lihotzky, for example, prepared the manuscript for her Memories of the Resistance at a moment when secondary source material in resistance studies was dominated by hetero-patriarchal norms. Her book was an effort in documenting working-class women’s lives, revising conventional notions of assistance and docile service to daring male dissidents. The appendix, with more than one hundred names and biographies, portrays female resistance fighters in a defiant light and with complexity and nuance. A committed communist, Schütte-Lihotzky wrote her recollections when the limits of communism had become increasingly clear, but also when Social Democrats and conservatives in Austria persisted in minimizing the role of the Communist Party as a force of resistance to National Socialism. This was a time characterized by a continued culture of erasure and forgetting in Austria—it was not until 1991 that an elected official recognized and apologized for Austria’s role as main perpetrator of the Holocaust.

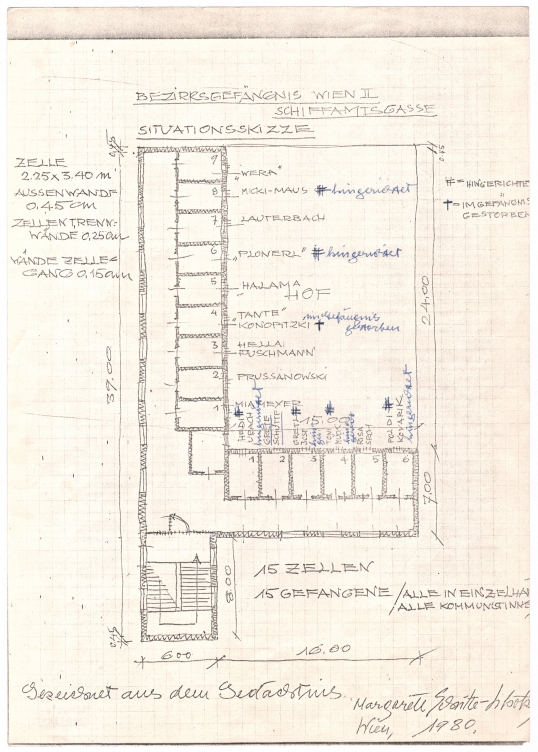

Fig. 16. Schütte-Lihotzky, drawing from memory of the Schiffamtsgasse prison, Vienna, 1980. University of Applied Art, Collection and Archive.

Included in her book is an architectural drawing that Schütte-Lihotzky reproduced from memory in 1980 (fig. 16). The plan represents the cells at the Gestapo prison at Schiffamtsgasse where she spent more than a year with fourteen other female resistance fighters. Next to individual cells in the plan, she inscribed the women’s names, some of them her closest confidants. The document reads: “Poldi Kovarik, Risa Srch, Toni [Antonie] Mück, Gretl Jost, Grete Schütte, Hedi [Hedy] Urach, Mia Meyer, [Else] Prussenowsky, Hella Puschmann, ‘Tante’ [Theresia] Konopicky, [Beatrix] Halama, ‘Plonerl’ [Apolonia Binder], [Antonie] Lauterbach, Micki Maus, ‘Wera.’” Schüttte-Lihotzky indicated pseudonyms or prison names alongside legal names—many of which she was able to locate only after 1945. The names and the act of inscribing them in space reveal a politics of historiography that may not be immediately apparent. Seen together, these women’s names and the biographies housed in the appendix illustrate a range of resistance activities, some of which destabilize normative gender roles. Schütte-Lihotzky includes women who carried out “spontaneous acts of resistance” and smaller dissident tasks, as well as those who devised targeted strategies and open, active, and armed resistance. Her book was one of the first to give sustained attention to questions of gender and class in resistance work.127

The inscription “Micki Maus” refers to a person whose legal name Schütte-Lihotzky was unable to uncover at the time of her book’s publication. The inclusion of the prison pseudonym, however, enabled resistance historian Willy Weinert in 2013 to match this clandestine prison name to the identity of Anna Herbrich (1904–1943). Herbrich, who was a seamstress by profession, was executed by the Nazis in Vienna in 1943. In 2013, her grave at the Wiener Zentralfriedhof became part of a designated national memorial.128 Schütte-Lihotzky’s mention of her as well as her detailed work of compiling more than one hundred names of female resistance fighters in the appendix shows a care towards people that extends to archives.

The pseudonym “Wera,” used throughout the book, memorialized Schütte-Lihotzky’s friend Maier Mayer. Maier Mayer was active in the organized resistance against Augusto Pinochet in her native Chile when the memoir was published. Her personal details, for this reason, could not be revealed or publicly remembered.129 Schütte-Lihotzky’s multiple postwar attempts to have memorials built almost always failed, but it is possible to think of Memories of the Resistance as an attempt at a textual memorial.

In addressing the question of memory, in conclusion, I would like to introduce one more person: the fictional character Emil Scheffler in Elisabeth Freundlich’s 1986 book of stories, Dark Times (Finstere Zeiten). The book, published half a decade before her autobiography appeared, is an effort to create an archive as well, but it is distinct in nature and objective from Schütte-Lihotzky’s politics of drawing and creating appendices. Four short stories, one of them completed immediately after 1945, chronicle an emergent culture of forgetting.130 The book fictionalizes individuals who closely resemble people in Freundlich’s life. A protagonist never fully matches the biography of a single person but instead often appears as a composite.131

Freundlich wrote the story “The Philosopher’s Stone,” the first story in the book, in New York in 1947. The narrative follows a group of people living in Paris in the aftermath of the Second World War. It is gradually revealed that all the characters are unrelated but nevertheless part of an extended kinship network. The protagonists—who are former resistance fighters and non-resistance fighters, and Jewish and non-Jewish—are a housekeeper, the single mother of an adopted boy, two archivists, and several youths. They are at odds about what to do with a trove of documents that belonged to the boy’s father, Emil Scheffler, who produced clandestine writing as a form of resistance in a concentration and extermination camp before he was murdered in 1945.132 The extended family struggles with the question of whether the materials should be given to the boy to remember his father, or formally archived. When the boy’s foster mother insists that the documents be given to her adopted son, the story culminates in a question about the politics of archives. The passage speaks to the documentation of resistance activity, the experience of exile, and the complexities of kinship after the Holocaust. “Our writings and pamphlets today are already of historic value,” Freundlich writes in the short story.133 She continues:

The voice of the opposition—which was too weak—became captured in them. In the future one will leaf through them with the caution and care with which one leaves through precious illuminated manuscripts. They were created with the same diligence, with the same dedication to something, that is more than we are alone. And even if the individual pieces moved by the thousands through the printing press, and thousands were sent, only very few pieces survived. That is why they have great value for posterity. For us, bearers of a decade-long futile struggle, and for those coming after us, who, because this struggle was really in vain, must build a new land from the rubble and ashes, these documents should establish a tradition. If I nevertheless ask to hand over a few pieces of this collection to the son of our Emil Scheffler, I do so because we were never concerned merely with the preservation of paper, but always, and above all, with humans.134

The passage illustrates that Freundlich’s protagonists form a system of care for one another. While this form of care is not without its problems, the characters share beliefs and values. Among these is the idea that documents have both personal and historical meaning and that archives are in the service of humans to preserve achievements and memories of their lives. The story is characterized not by a narrative of defiant defense of country, which structures many communist memoirs, but by a notion of belonging. Unlike Schütte-Lihotzky, who draws on a rhetoric of radical refusal in her memoir, Freundlich is clear about the meekness of the Austrian resistance and never sentimental about life in Vienna. Freundlich’s protagonists, many of whom are multilingual, represent an exilic kinship bound together by experiences of irreconcilable harm, displacement, and mass murder in the Holocaust.

Freundlich returns to the themes of loss and grief, as well as kinship and care against the backdrop of the Holocaust, in a later story set in a small Austrian town with seemingly unrelated characters. The narrative chronicles individuals living in the shadow of a concentration camp and the resistant work of an interned man. The man at the center of the narrative only appears through the voices of the townspeople. Although it is not explicitly stated, this character bears a strong resemblance to Emil Scheffler in “The Philosopher’s Stone.” He is described as a person who cared for his friends, intellectually and emotionally, and who collected information and gave others hope and courage.

To argue that Freundlich’s fictional character is a portrait of Otto Heller would be simplistic, but certain elements of their biographies correspond in important ways.135 Freundlich was deeply concerned with setting the historical record straight on Heller’s role in the Austrian resistance. At the 1980 conference “Vertriebene Vernunft” (Deported Reason), she showed to scholars of exile literature that Heller—and not Erwin Zucker-Schilling, as they had long assumed—had been the editor-in-chief of Nouvelles d’Autriche. Many of the articles were penned by one “Anton Wiener” and Zucker-Schilling had used the pseudonym “Hugo Wiener” in the 1930s.136 It is likely that Heller had substantial input on the articles signed “Anton Wiener,” since Zucker-Schilling was not fluent in French.137

Freundlich’s approach in Dark Times is a nuanced model for the writing of counter-hegemonic narratives that differs drastically from that of Schütte-Lihotzky in Memories of the Resistance. Dark Times reminds readers that to reflect critically on both exile and resistance is to contend not only with questions of gender, class, and political affiliation, but also with complex constructions of culture, religion, identity, and difference. Moreover, the people that Freundlich remembers consistently defy gender norms. Men who cared for one another, for example, are not held to binary gender standards and often undertake “feminized” labor such as consoling, counseling, and cooking for communities. While Schütte-Lihotzky wrote critically about gender and sexuality when it came to histories of women in the resistance, she ultimately shied away from discussions of how men defied or conformed to gender norms or how they used their bodies in dissident work. As the case of Hedy Urach, her close friend in internment, makes clear, Schütte-Lihotzky maintained binary notions of gender in her memoir. Schütte-Lihotzky never mentions that Urach, who was one of the most daring female activists, presented as deliberately masculine, nor does she address the fact that those who did not perform hetero-normative displays of gender or sexual identities were particularly vulnerable to the Nazi terror apparatus. Dark Times, by contrast, suggests that individual histories must be represented in all their complexity while at the same time being attentive to identity. Freundlich’s work to memorialize Heller’s life—in both overt engagement with historical discourse and in an oblique fictional gesture—is an acknowledgement that his history embodies a shared history of Jewish suffering. Histories of exile and belonging are histories of individuals, but also of entire families and generations.

Finally, Freundlich’s essay also stresses that while constructions of identity are complex, they should not be essentialized. Austrian histories and historiographies of exile and resistance often minimize Jewish achievement and suffering, subsuming it under affiliations to political parties and nations. Hannah Arendt’s work is contentious in the historiography of the Holocaust today, but in her speech, “On Humanity in Dark Times: Notes on Lessing,” she makes a note that still carries weight. In the speech she emphasizes the need to recognize constructions of subjectivity when it comes to histories of resistance, exile, and the Holocaust, writing that “one can only resist in terms of the identity that is under attack.”138 In the same lecture she warns that because anti-Semitism was intrinsic to National Socialism, to minimize the complex ways in which identities shaped experiences of emigration, resistance, and internment or to completely disregard it is to reenact the violence of anti-Semitism. Histories of resistance and exile that expand to spatial investigations therefore must continue to address difference and a version of intersectionality in which Jewish identity remains the central category.139 Such attention was given only minor consideration in histories and memoirs in and of the Communist resistance.

In writing this essay, I therefore attempted to work against certain ingrained biases that shape the historiography of resistance. Juxtaposing forms of resistance that relied on political affiliations and national frameworks with cultural modes of dissidence prompts reflection on how identities in histories of exile and resistance are constructed and how they enter our present. Analysis of spaces can uncover the category of identity while resisting the impulse to fix varied subjectivities or to follow party hierarchies.