Birthing, Borders, and Bodies: American Crossings

Exterior view of the Holy Family courtyard.

Photo by Lori A. Brown.Because being aware of what is happening in our era and choosing to do nothing about it has become unacceptable. Because we cannot allow ourselves to go on normalizing horror and violence. Because we can all be held accountable if something happens under our noses and we don’t dare even look.

—Valeria Luiselli, Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions, 2017

Fig. 1. Border wall.

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs were taken by Lori A. Brown.

Birthing clinics, respite centers, and shelters provide powerful evidence of ever-evolving grassroots networks that support individuals who have managed to enter the United States.1 The users of these spaces charge them with radical potential by defying geopolitical boundaries, as immigration, border security, and women’s rights collide with neoliberal economic policies. Women, parents with children, and unaccompanied minors come to occupy multiple locations, subverting the myth of borders as fixed and impermeable. They use their bodies to transgress nation-states in order to create a different future for their children and themselves, radically reconfiguring the space of the family through trans-border locationality.

This interpretation of spaces established to provide support and care for those entering the United States offers a critique of US immigration and economic policy across the Trump and Biden administrations.2 This essay focuses on spaces that support pregnant women and unaccompanied minors as well as parents and their children. As a feminist architect and activist bringing together my training and politics, I aim to connect and make visible spaces of care in the borderland region of the Rio Grande Valley. These spaces are often managed by non-profits or religiously affiliated institutions. I specifically focus on Holy Family Birth Center, the Sacred Heart Catholic Church, and the Humanitarian Respite Center (HRC).3 Note also that I provided unremunerated labor for the Holy Family Birth Center and the HRC: the director of Holy Family requested a design proposal to create more patient privacy in the medical clinic, which I provided pro bono, and I volunteered in the HRC’s warehouse, sorting material donations, and in the course of this work also proposed plans for more efficient systems of storage and retrieval. Regardless of their complex politics, these organizations’ commitment to a trans-border politics that is ultimately supportive of migrants is the focus of this essay. The trans-border imagination is a driving force for migrants, and it undergirds an architecture that may be aesthetically unremarkable but is unquestionably historically significant. My work, even as it inhabits a spectrum of power, is conceived in solidarity with this imagination.

I build on conversations with those in caring roles rather than the migrants themselves. It quickly became apparent to me how traumatized many migrants and their children were. Most were recently released from border detention. I recognized the risk of introducing further trauma and did not think it was appropriate to interview anyone other than those providing care to migrants. The nuns involved in the birthing facilities and humanitarian respite center stated that their priority was care. They discussed agreements made with border patrol agents to access people in need of care dispassionately and in a matter-of-fact way—never in political terms.

Exploring how local conditions and the hybridizing of cultures defies nation-state boundaries, I turn to the materiality of birthing clinics and refuge centers, taking a cue from the interdependent material and spatial histories that Sarah Lopez explores in migrant detention centers, within which, as she observes, Texas produces a distinctive spatial version as it leads the United States in their creation.4

Fig. 2. Humanitarian Respite Center, McAllen, Texas.

My analysis directly challenges federal immigration policies, and in particular their turn toward more nationalist tendencies under the Trump administration. During President Trump’s time in office, mobility significantly decreased for undocumented people through a system of highly policed and surveilled border checks within one hundred miles from any US border. Now, under the Biden administration, one that has stated it will take a more “humane” approach towards immigration policy, some of these policies have begun to be reversed and some of the travel restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic have been lifted.5 A few examples include preserving deportation relief that allows immigrants who have received Medicaid to receive green cards, lifting visa restrictions, allowing more immigrants into the US, and providing a pathway to citizenship for immigrants already in the country.6 Probably the most immediate and consequential policy change since President Biden came into office is that unaccompanied minors are allowed to enter the US, a development that has seen the largest number of unaccompanied minors in the past twenty years enter from Mexico.7 Policy changes impact where and how migrants are cared for once they enter the US. The spaces discussed here provide critical care that is perceived by the security state as frontline work. The dramatic fluctuation of people requires an agile and responsive network of on-the-ground care providers who can adroitly and creatively accommodate lives under threat for crossing a border.

Holy Family Birth Center, Weslaco, Texas8

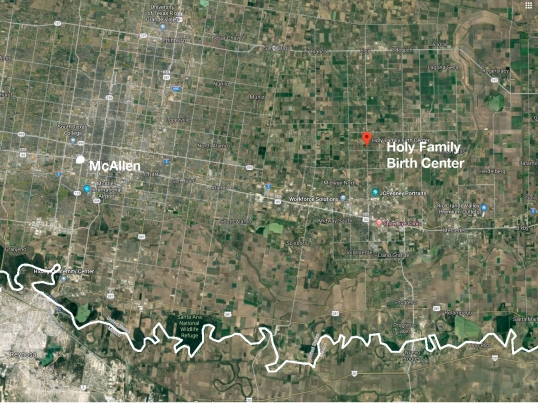

Fig. 3. Holy Family Birth Center, Weslaco, Texas.

Google Maps and Lori A. Brown.

Founded in 1983 and located approximately eighteen miles east of McAllen, Texas, Holy Family Birth Center is the only birth center in the Rio Grande Valley operated by certified nurse-midwives and is the longest free-standing licensed birth center in Texas.9 Holy Family provides a full spectrum of obstetrics and gynecological care. Sister Angela Murdaugh, one of the center’s four co-founders, all of whom were nuns, was a certified nurse-midwife who practiced in health clinics in the Rio Grande Valley in the 1970s. As she served farm workers, many of whom had migrated from Mexico, she became aware of the need for prenatal care for pregnant women. She and the other nuns were introduced to a Mexican practice in which “home” births actually take place outside the home, with care provided by local parteras, or midwives. Rather than a midwife traveling from birth to birth, pregnant women travel to a midwife to give birth. A midwife would often either maintain a room in her house or create a small casita behind her house for birthing. Sister Angela decided to follow in the footsteps of many of the local parteras and create a birthing center.10

Fig. 4. Holy Family Birth Center compound, Weslaco, Texas.

Google Maps.

Holy Family Birth Center is situated within a nondescript and picturesque rural southeast Texas farming landscape. It is comprised of a series of small wood-frame buildings surrounding a shaded interior landscaped courtyard connected by several walkways. The diocese owns the land and loans it to Holy Family explicitly for use as a healthcare facility; if or when it ceases being a healthcare facility, the land will revert back to the diocese. The nuns knew, or rather hoped, that the services they were providing would not be needed indefinitely and therefore, from the outset, they considered what would happen when Holy Family ceased to exist. This sense of impermanence impacted the architecture; all buildings were designed to be easily deconstructed and moved, and materials sold off.

The nuns cleared the farmland and built the structures one at a time. Because they had so little money, they did some of the building themselves.

Fig. 5. Exterior view of the Holy Family birthing rooms and courtyard walkway.

The complex grew incrementally to include dormitory-like housing for staff and volunteers and a building with a kitchen and dining room.

Fig. 6. Exterior view of the Holy Family kitchen and dining building.

The covered breezeway provides shade and also creates open, cooler zones. The facility includes a medical office with patient rooms, a classroom, a kitchen and dining area, three birthing suites, housing, a chapel, a playground area, and space for a vegetable garden.

Fig. 7. Exterior view of the Holy Family classroom.

The overall site plan speaks to an understanding of the body’s natural rhythms and it is designed to support what can be a long and arduous birth process. The nuns considered how patients move through the site, and when and where families can be with them for support. None of the original buildings were air-conditioned, and the outdoor shaded courtyard space creates cooler zones for women in labor walking through their contractions.

Fig. 8. Exterior view of the Holy Family courtyard.

Sister Angela describes the original birth room layout as one designed to allow a midwife to attend to two births simultaneously, with two rooms separated by a single door. When I visited, the three birthing suites were under renovation. Each room now includes space for family members to be present during birth. In interviews with staff, it became clear that everyone values the spatial arrangement of the buildings in relation to the exterior spaces and understands how these spaces work together to facilitate and support their work and a patient’s experience. Although the nuns were not trained in architecture, they understand how space participates in the support and care of their patients and the community. Through an economy of means that prioritizes material and ecological sensitivity to their surroundings, the nuns created a facility that spatializes their commitment to providing care with the lightest footprint possible.

Originally established as a non-profit organization, Holy Family provides birthing care for the mostly underserved women and families in the Rio Grande Valley who generally live far from a hospital or clinic. Many patients are either under-insured or have no insurance whatsoever. To ensure access, Holy Family created a sliding payment scale including an option that combines cash payment with one hundred hours of volunteer service work. Eventually, Holy Family expanded to serve middle- and upper-middle-class patients who seek a non-hospital setting for their birth.

The ease and flexibility of border crossing varies for patients. If a Mexican patient has a visa, border crossings can be quite fluid. I was told that some patients found crossing back into Mexico after birth to be more difficult.11 Often, Mexican women request a letter from Holy Family stating that they have “paid in full” and have not used any US government funds for the payment of medical services. The director of the center thinks letters of this kind are not strictly required by Mexican law, but that they reduce the annoyance that can be created by border patrol agents.

During orientation sessions with Holy Family, pregnant women often ask about the protocol for obtaining a birth certificate for their child. Mothers who give birth at Holy Family have every legal right to receive an American birth certificate for their United States–born child.12 On average, the process for applying and receiving a birth certificate in Texas can take six to eight weeks.13 Holy Family’s director mentioned that some women have encountered difficulties in the process. She often hears her patients repeat false information about the application process, including that an expectant mother needs US identification in order to apply for a birth certificate. One can imagine the spreading of false information is a tactic to deter undocumented mothers from filing for birth certificates.

The director also noted that many of Holy Family’s Mexican patients do not want to remain in the US after giving birth; they prefer to return to Mexico, to their families and their fully established lives. Many do hope their child might one day attend college in the US, and by securing citizenship for their US-born child they provide them with a significant advantage in this regard. This reality counters mainstream media messaging that proliferates an image of migrant families using their children to obtain US citizenship and abuse American social services.14 In recent years there has been an increasing shift in migrants’ country of origin, with fewer originating from Mexico and more from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Increased migration from these countries, together commonly referred to as the Northern Triangle of Central America, is prompted by high rates of violence, natural disasters, poverty, and government corruption. These factors constitute the “push” for people seeking to leave, and are combined with what the US is seen to offer—the “pull”—which includes economic, educational, and social possibilities. Research by the National Immigration Forum argues that, for Central American migrants in recent years, the factors that push outweigh those that pull.15 The Migration Policy Institute reports that immigrant labor force participation in the US is highest among Central American immigrants, at 72 percent, compared to all foreign-born (67 percent) and US-born populations (62 percent). Of those from Central America, immigrants from El Salvador and Guatemala have the highest labor force participation, at 74 percent.16

Many in the borderland exist in a trans-border locationality. Gloria Anzaldúa names this in-between culture la mestiza, one between two others, producing a third. La mestiza is a struggle, a cultural collision between the United States and Mexico, a hybrid.17 This culture exists not in oppositional terms, as a predominantly white US culture versus a Mexican culture, where both register at odds with indigenous cultures, but rather as a true mixing. As she writes, “It is not enough to stand on the opposite riverbank shouting questions, challenging patriarchal, white conventions. A counterstance locks one into a duel of oppressor and oppressed; locked in mortal combat, like the cop and the criminal, both are reduced to a common denominator of violence.”18 This counterstance gives way to liberation and the creation of a “new consciousness”—at some point one must leave the opposite bank. For Anzaldúa, great potential resides within this space. Once we abandon the binary, we can occupy both sides simultaneously, creating a new territory altogether; “[t]he possibilities are numerous once we decide to act and not react.” She imagines myriad possibilities of the borderlands. La mestiza embraces contradictions and ambiguities.19 This powerful liminal space counteracts the xenophobia of hard borders, exclusion, and immigration that works to limit the mobility of certain bodies in the United States. Openness and acceptance are vital for this new space to evolve and thrive.

Borders are not only legal, political, economic, and cultural entities, but also the lived experiences of those who inhabit these liminal zones.20 Anzaldúa’s work provides a framework for considering the complex and layered border conditions that the women who give birth at Holy Family and their families inhabit. Those living in this region occupy in-between cultural and social spaces and embody multiple identities. For Anzaldúa, borderlands speak to the space where “antithetical elements mix, neither to obliterate each other nor to be subsumed by a larger whole, but rather to combine in unique and unexpected ways.”21 Furthermore she states that, “Borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge. A borderland is a vague and an undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary.”22 This “unnatural boundary,” one under constant US surveillance, contestation, and ever-greater militarization, attempts to reduce and curtail its undefined regions. But hundreds of thousands defy this constriction.

Sacred Heart Catholic Church and Sister Norma, McAllen, Texas23

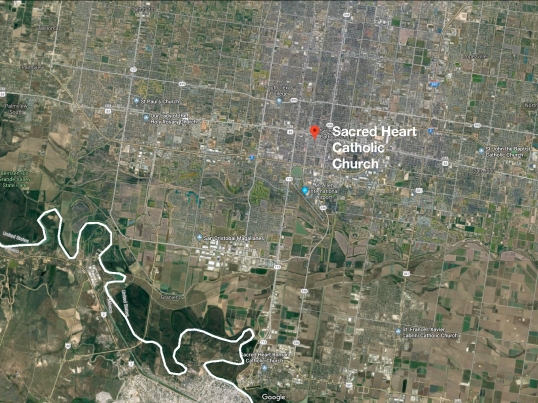

Fig. 9. Sacred Heart Catholic Church, McAllen, Texas.

Google Maps.

Sacred Heart Catholic Church is located in the city of McAllen, Texas. The church complex occupies an entire downtown city block and is only about a block and a half from the bus station.

Fig. 10. Sacred Heart Catholic Church, McAllen, Texas.

Google Maps.

The property includes the church, a parish hall, additional spaces for offices and classrooms, and a large parking lot behind the primary group of buildings. When I visited in spring 2017, the parking lot contained temporary air-conditioned tents and showers.

Fig. 11. Temporary overflow air-conditioned tents in the parking lot of Sacred Heart Catholic Church, McAllen, Texas.

The city of McAllen occupies a critical position within the movement of migrants into the US. The Ursula Processing Center, the country’s largest immigration processing center, holding over one thousand detainees, is five miles away. The extreme inhumane conditions detainees were forced to endure in this facility caused enormous public outcry after images were leaked to the press in 2018. Due to the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” policy, detainees also included children who had been separated from their parents. As described by NBC journalists who were allowed access, this 77,000-square-foot facility separated detained families and unaccompanied minors by family status, gender, and age. There are pods for girls who are seventeen and under, boys seventeen and under, mothers with children, and fathers with children.24 In June 2019, immigration lawyers and pediatricians visited some of the other detention facilities along the southern border and found shocking conditions. Children’s health care needs were not being met. They were not receiving enough food, were unable to get enough sleep, and were under severe stress in the unhygienic conditions.25

Sister Norma and Sacred Heart were instrumental in establishing facilities to provide care for some of these unaccompanied children, pregnant women, and women with children once they were released from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the immigration detention centers. Sister Norma observed that those just released from detention were in dire need of basic hygiene, food, clothing, and sometimes medical attention.

Fig. 12. Temporary showers in the parking lot of Sacred Heart Catholic Church, McAllen, Texas.

Fig. 13. Temporary donations in the basement of Sacred Heart Catholic Church, McAllen, Texas.

As she said, they had endured a great deal and she and the volunteers want to help restore their human dignity. Initially, groups of migrants were dropped off at the bus station and required to wait—sometimes for over twenty-four hours—for a bus that would take them to their sponsor somewhere in the US. For the small number of migrants who do not have family in the country, a different local shelter in the Rio Grande Valley provides housing until a sponsor can be found.

When I first visited in late April 2017, Sacred Heart was noticing a significant downturn in migrants crossing into the US. Sister Norma thought this reflected the Trump government’s new policy. In the past, Sacred Heart could receive as many as four hundred people daily. However, during my time there, they were receiving between fifty and one hundred people each week. She thought the change in the administration’s policy also affected how traffickers were operating. The US government’s policies were producing greater fear for migrants attempting to cross the border. She mentioned that pregnant women are treated differently by CBP due to their increased health risks; CBP does not want to detain these women for long. Often, Sacred Heart receives women who recently gave birth and provides extended care for several days so they can rest and recuperate. Sometimes, volunteer families bring these women and their newborns home and provide care for longer periods of time before they travel onward. Within the church complex, Sacred Heart created other support spaces. These include a makeshift medical clinic converted from a dining hall closet, a sleeping space adapted from a storage closet, and a shower altered from a cleaning closet, as well as air-conditioned tents in the parking lot that can host migrants once the capacity of the church basement has been exceeded. These makeshift spaces demonstrate a capacity for resourcefulness and an ability to create with minimal spatial and financial interventions.

Fig. 14. Temporary medical clinic in Sacred Heart Catholic Church, McAllen, Texas.

Humanitarian Respite Center

Fig. 15. Humanitarian Respite Center, McAllen, Texas.

Google Maps.

The migrant support services spearheaded by Sister Norma at the Humanitarian Respite Center were forced to relocate their facilities, and in 2017 they moved to their current site in downtown McAllen. This space is just across the street from the bus station and therefore easier for migrants to access.

Fig. 16. Exterior view of the Humanitarian Respite Center, McAllen, Texas.

My most recent observations stem from a week I spent volunteering at the HRC during the summer of 2019. The enormous facility is staffed by Catholic Charities employees and volunteers from around the world. At the time I arrived, the HRC received on average between seven hundred and nine hundred migrants each day, with the facility’s maximum legal occupancy set at 1,254 people. Once migrants were dropped off at the bus station by CBP, they were either escorted or found their own way to the HRC. Volunteers from Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin, and even Spain assisted the migrants during the week I spent there.

The layout of the center, a former dance club, is well suited to the organization’s activities. Due to financial constraints, few spatial alterations have been made. The primary space includes an entrance with twenty-four-hour security, a check-in desk area, and a pharmacy station staffed by both nurses and non-medical staff that provides toiletries for showers, toilet paper, and over-the-counter medicine, but—as I discovered from two volunteer nurses—not pregnancy tests. The upper floor houses a small office that has been converted into a chapel, a large seating area that transforms into the resting and sleeping zone every night, and an in-take area staffed by legal advisors. Recently arrived migrants wait on the former dance floor, now scattered with chairs, and in an adjacent play space with toys and a big-screen television showing cartoons, until their names are called. At around 8 p.m. every evening, mattresses are unstacked and placed on the floor so that everyone has a space to sleep. Between 7 and 7:30 a.m. every morning, the mattresses are re-stacked around the perimeter walls to create space for people to wait and rest during the day.

The space adjacent to the large waiting area includes showers with specific times for male and female use. The area at the back of the building includes the service kitchen and dining area on one side and an all-ages clothing and shoe dispensary on the other.

Fig. 17. Donation warehouse, Humanitarian Respite Center, McAllen, Texas.

The part-time medical clinic is located upstairs and staffed by volunteer doctors. The end of the warehouse contains the space where all donations are received, sorted, and organized.

Fig. 18. Wall of diaper donations, Humanitarian Respite Center, McAllen, Texas.

Fig. 19. Bins for organizing donated goods, Humanitarian Respite Center, McAllen, Texas.

Migrants can spend anywhere from a few hours to several days in these two ground-floor rooms. Upon entering the space, it quickly becomes apparent that the building’s ventilation system is extremely poor, especially considering the large number of people who make use of the facility. According to the volunteer director, some migrants arrive with colds due to the frigid conditions in detention or catch a cold while at HRC. Combined with the COVID-19 pandemic and Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s ban on mandates for vaccines and masks in schools, this situation creates serious health risks.26

In July 2019, hundreds of migrants passed through HRC on a daily basis. However, after several days, these numbers began to decline noticeably. HRC staff associated the drastic reduction in numbers with the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy—officially titled Migration Protection Protocols—which required asylum seekers to live in Mexico while awaiting an immigration appointment. This policy began in early 2019, but its effects began to be seen only in the summer. A backlog of roughly eight hundred thousand cases results in an extremely long wait before an individual is called to court.

Historically, anyone claiming asylum would reside in the US while awaiting their court proceedings.27 The Trump administration’s policy sought to deter people from making asylum claims. The effects of this policy are nowhere more evident than at the Mexican border zones, where migrants are forced to wait in any space they can find—on streets and sidewalks, in shelters, or in empty spaces. For the most part, migrants must be self-reliant in covering their basic human needs, including accessing food and water and contacting relatives. Safety is a major concern. Shelters have been created in these areas to support migrants while they wait, but the facilities are generally unable to fulfill the demands of the thousands who continue to arrive at the border.28

The HRC is aware that shelters in Mexico do not have the space, resources, and flexibility to handle the numbers of people seeking care. The HRC partners with other local organizations and private groups to create overflow space and makeshift accommodations and provide food services and shower facilities. The volunteer director mentioned that Mexican news outlets highlight the need for greater overflow capacity for migrant populations and emphasize that finding shelter becomes an individual effort. This creates situations where vast numbers of migrants are living on the streets and in whatever abandoned buildings they are able to find.29

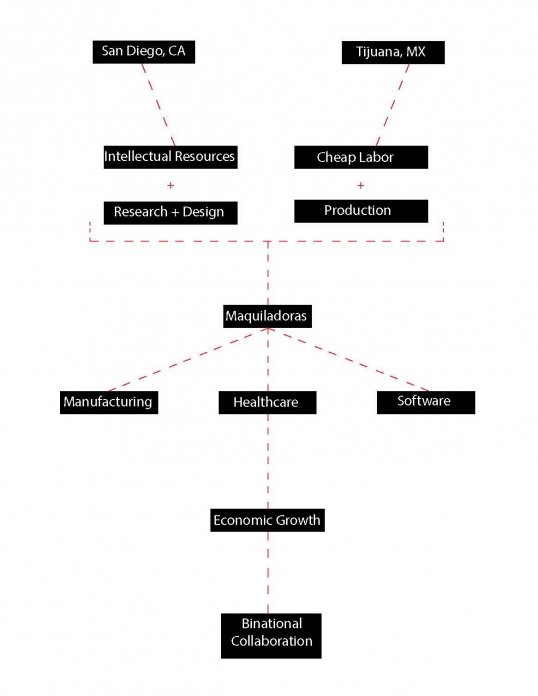

The Economics Producing Massive Migration

Silvia Federici’s work on labor, capital accumulation, globalization, and their effects on women, both historically and in the present day, provides a valuable lens through which to think about Latin American migrants who risk everything to enter the United States. Often, they are either quite impoverished or fleeing extreme violence and life-threatening situations. In either case, they bear some of the greatest effects of these economic policies; policies created to benefit transnational corporations through tax-free trade across borders. Federici’s historical analysis describes how changes in economic systems disproportionately affect women.30 Globalization produces, according to Federici, the “feminization of poverty.”31 Although women are “integrated” into this economy, specifically given the surge in manufacturing jobs that the North American Free Trade Agreement produced, the current phase of globalization has resulted in the massive numbers of Central Americans and Mexicans fleeing their homelands in pursuit of employment and safety.32 Thousands hope to forge different futures, crossing into the US and overflowing the capacities of shelters and border-processing stations. Religious, non-profit, and private organizations—like the birthing centers I have described here—have responded to fill the immense holes left by retreating government policies. The creative flexibility and adaptability of those providing care demonstrate how buildings can be re-imagined to perform in many unintended ways and uses. Churches provide meals, and social networks work with organizations and private citizens to locate food, showers, and spaces for sleeping. The HRC receives such enormous quantities of donations that, at the time I volunteered, they were finding a way to send goods to a shelter across the border. Although support for those in need is created, those most impoverished are most impacted by globalization and are forced to leave their country and migrate.

Fig. 20. San Diego–Tijuana bi-national relationship.

Juliet Domine.

With the flaming of xenophobia during the Trump administration, the border has become ever more militarized by both federal and state governments as well as by local vigilantes. Anzaldúa describes the historical border relations between Mexico and the United States as a long relationship moving between peaceful and productive intersections to war and pillaging.

Fig. 21. U.S. Customs and Border Protection secure the San Ysidro Port of Entry from Mexico.

U.S. Custom and Border Protection, 2018.

As Anzaldúa writes: “Hunters in army-green uniforms stalk and track these economic refugees by the powerful nightvision of electronic sensing devices planted in the ground or mounted on Border Patrol vans.”33

Fig. 22. Border vigilante.

Brandon Quester and ineswource.

These tactics escalated during the Trump administration, alongside the commitment to expanding the border wall; the deployment of enhanced surveillance technologies such as radar, surveillance towers, thermal imaging, facial recognition software, biometric iris scanning, and the possible creation of a DNA database; and the drastic reduction in the annual numbers of immigrants the US willingly accepts.34

Counter-Movements

In Gore Capitalism, philosopher and activist Sayak Valencia develops a transfeminist discourse that engages the complexity of the Third World (the term she uses). This discourse distinguishes itself from white First World feminism, engages queer subjectivities with alliances outside of essentialized identities, and provides a critique of the logics of capitalism and its persistent production of violence in parts of the Third World. Valencia names this particular violence “gore capitalism”—a term borrowed from genres of extreme cinema that exploits vulnerable bodies, uses extreme violence, mutilation, and desecration—because it has been created through and shaped by globalized, capitalist economic systems that produce conditions wherein certain bodies are deemed disposable and without value.35 Valencia joins Judith Butler in arguing that “it seems more crucial than ever to disengage feminism from its First World presumption and to use the resources of feminist theory and activism to rethink the meaning of the tie, the bond, the alliance, the relations, as they are imagined and lived in the horizon of a counter-imperialist egalitarianism.”36 This requires us to imagine a different future beyond the current spatialization of the nation-state serving the logics of late-stage capitalism. Trans-border economies and local alliances provide ways forward, as do hybridities of borderland politics, systems of care, and the inevitable necessity of ecological interdependence across the region.

Fig. 23. Border wall construction mock-ups.

U.S. Custom and Border Protection, 2017.

Central Americans and Mexicans occupy margins as they make their way into the US and, once there, their bodies and mobilities act against the hegemonic state. Through something as “simple” as childbirth, women counter the physical limitations of what a border represents and attempts to reinforce. Humanitarian shelters also contribute to these abilities. In writing about how many Black Americans choose to occupy the margins rather than the center because of structural inequalities, bell hooks suggests ways to think about the border, migration, and spaces of possibility.37 For hooks, the act of moving requires one to “confront the realities of choice and location.”38 “Politics of location” are vital because they include the experiences of those who are working to counter hegemonic discourses:

Within complex and ever shifting realms of power relations, do we position ourselves on the side of colonizing mentality? Or do we continue to stand in political resistance with the oppressed, ready to offer our ways of seeing and theorizing, of making culture, towards that revolutionary effort which seeks to create space where there is unlimited access to the pleasure and power of knowing, where transformation is possible? This choice is crucial. It shapes and determines our response to existing cultural practice and our capacity to envision new, alternative, oppositional aesthetic acts. It informs the way we speak about these issues, the language we choose.39

Fig. 24. Not-To-Scale Studio, 1,954-mile-long dining table, United States–Mexico border.

Not-To-Scale Studio, 2017.

Fig. 25. Rael San Fratello, Teeter-Totter Wall, Ciudad Juárez and El Paso.

Rael San Fratello, 2019.

hooks reminds us that cultural interventions and aesthetic actions can be powerful and necessary responses to power. These actions productively disorient, reorient, and provoke us to imagine differently.

Although I reside on the US side of this imperial division, I have sought to connect and make visible spaces of care such as the Humanitarian Respite Center and Holy Family Birth Center. Writing this sort of history works against the United States’ ongoing colonizing, imperial efforts at its southern border regions, where the government decrees that some lives are not as worthy as others.40 I want to acknowledge the immense strength and courage it requires to come to the US, often under immense hardship, and to stand in solidarity and political resistance with people who need care when they give birth or when they are seeking asylum, in creating a better economic future for themselves and their families. And, along with those who provide care and support, they are defying nation-state definitions of the Texas borderlands. The interwoven complexities of the United States–Mexico border region continue to point the way toward a future full of radical potential.

✓ Transparent peer-reviewed

Lori A. Brown, “Birthing, Borders, and Bodies: American Crossings,” Aggregate 10 (November 2022), https://doi.org/10.53965/CFOX5052.

- 1

In particular, histories of United States border relations, immigration laws, and policies. See Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014); Greg Grandin, The End of The Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (New York: Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company, 2019); Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2007); Susan J. Terrio, Whose Child Am I? Unaccompanied, Undocumented Children in US Immigration Custody (Berkeley: University California Berkley, 2015).

↑ - 2

This essay is part of the larger ongoing research project Birthing, Borders, and Bodies. The project examines how space is governed and controlled, and how immigration policies and citizenship rights influence the spaces organizations establish to provide care for pregnant women and immigrants seeking asylum. It explores where these organizations are located as well as at what scales they operate and how their capacities grow and develop. The project’s focus is on how power operates and responds spatially via the manipulation of borders, the identities of nation-states, the myths and representations of US borders in the media, and the geography of borderlands.

↑ - 3

I have addressed the topics of abortion clinics and migration in writings published elsewhere, including: “‘Like Some Kind of Legal Houdini’: Abortion Access and the State in Garza,” The Avery Review, October 2021, https://averyreview.com/issues/54/legal-houdini; “Don’t Mess with Texas: Abortion Policy Texas Style,” in Abortion across Borders: Transnational Travel and Access to Abortion Services, eds. Christabelle Sethna and Gayle Davis (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2019), 172–200; “On the Critiques: Abortion Clinics,” in Architecture and Feminism: Ecologies, Economies, Technologies, eds. Hélène Frichot, Catharina Gabrielsson, and Helen Runting (London: Routledge, 2017), 281–291; Lori A. Brown, Shoshanna Ehrlich, and Colleen MacQuarrie, “Subverting a Promise: Anti-abortion Policies and Activism in Canada and the United States,” in Canadian Abortion Politics: Twenty-Five Years after Morgentaler, eds. Tracy Penny Light and Shannon Stettner (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2017), 239–261; “Zoned Out: Buildings and Bodies,” Harvard Design Magazine 41 (2015), “Family Planning”: 157; and Contested Spaces: Abortion Clinics, Women’s Shelters and Hospitals (Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, 2013).

↑ - 4

Sarah Lopez, “From Penal to ‘Civil’: A Legacy of Private Prison Policy in a Landscape of Migrant Detention,” American Quarterly 71, no. 1 (March 2019): 106–107.

↑ - 5

Ashley Parker, Nick Miroff, Sean Sullivan, and Tyler Pager, “‘No End in Sight’: Inside the Biden Administration’s Failure to Contain the Border Surge,” The Washington Post, March 20, 2021.

↑ - 6

“Key Facts about US Immigration Policies and Biden’s Proposed Changes,” Fact Tank, Pew Research Center, March 22, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/22/key-facts-about-u-s-immigration-policies-and-bidens-proposed-changes/.

↑ - 7

Parker et al., “No End in Sight.”

↑ - 8

This information is based on interviews with employees at Holy Family conducted in April 2017.

↑ - 9

“Who We Are,” Holy Family Services, accessed July 5, 2019, https://www.holyfamilybirthcenter.com/about-us.

↑ - 10

Unlike the parteras, who practice independently of the medical system, Holy Family is connected with local physicians and can admit patients to a hospital in cases of emergency. Many of the original staff who worked at Holy Family were nurses and later became certified nurse-midwives. Due to this training, Holy Family recognizes that they are a medical practice and yet operate somewhat outside the establishment.

↑ - 11

The US border zone encompasses a one-hundred-mile stretch of land from the border. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, nearly two-thirds of the American population live within this region. Along the southern border, these checks are quite common and, in some cases, even routine. “The Constitution in the 100-miles Border Zone,” American Civil Liberaties Union, accessed April 13, 2021, https://www.aclu.org/other/constitution-100-mile-border-zone.

↑ - 12

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Chapter 2: Becoming a US Citizen,” in Policy Manual, Volume 12: Citizenships and Naturalization Part A – Citizenship and Naturalization Policies and Procedures, accessed July 6, 2019, https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-12-part-a-chapter-2. As the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website states, “Persons who are born in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction of the United States are citizens at birth.”

↑ - 13

Texas Department of State Health Services, “Ordering a Birth Certificate or Death Verification by Mail,” accessed July 6, 2019, https://www.dshs.texas.gov/vs/reqproc/Ordering-a-Birth-or-Death-Verification-by-Mail/.

↑ - 14

See Tara Watson, “Do Undocumented Immigrants Overuse Government Benefits?,” Econofact, March 28, 2017, https://econofact.org/do-undocumented-immigrants-overuse-government-benefits; American Civil Liberties Union, “The Rights of Immigrants,” accessed October 30, 2021, https://www.aclu.org/other/rights-immigrants-aclu-position-paper; Michael Fix and Ron Haskins, “Welfare Benefits for Non-citizens,” Brookings, February 2, 2002, https://www.brookings.edu/research/welfare-benefits-for-non-citizens/.

↑ - 15

There are many factors that create the impetus for migration. Some of the most harrowing include the fact that the Northern Triangle countries have some of the highest rates of violence in the world, high rates of poverty, and a high degree of vulnerability to environmental disasters caused by climate change. National Immigration Forum, “Push or Pull Factors: What Drives Central American Migrants to the US?,” July 23, 2019, https://immigrationforum.org/article/push-or-pull-factors-what-drives-central-american-migrants-to-the-u-s/. With regard to an increase in violence, see also United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Displacement in Central America,” accessed August 22, 2021, https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/displacement-in-central-america.html; and Congressional Research Service, “Central American Migration: Root Causes and US Policy,” August 22, 2021.

↑ - 16

Erin Babich and Jeanne Batalova, “Central American Immigrants in the United States”, Migration Policy Institute, August 11, 2021, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/central-american-immigrants-united-states.

↑ - 17

Anzaldúa, “Chapter 7: La conciencia de la mestiza,” in Borderlands/La Frontera.

↑ - 18

Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera, 100.

↑ - 19

Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera, 101.

↑ - 20

Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera, 99–100.

↑ - 21

Norma E. Cantú and Aida Hurtado, “Introduction,” in Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera, 5–6.

↑ - 22

Cantú and Hurtado, “Introduction,” 25.

↑ - 23

This information is based on interviews with Sister Norma conducted in April 2017.

↑ - 24

Jacob Soboroff and Julia Ainsley, “McAllen, Texas, Immigration Processing Center is Largest in US,” NBC News, June 18, 2018, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/mcallen-texas-immigration-processing-center-largest-u-s-n884126.

↑ - 25

Jeremy Raff, “What a Pediatrician Saw Inside a Border Patrol Warehouse,” The Atlantic, July 3, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2019/07/border-patrols-oversight-sick-migrant-children/593224/.

↑ - 26

Patrick Svitek, “Gov. Greg Abbott Bans Government Mandates on COVID-19 Vaccines Regardless of whether They Have Full FDA Approval,” The Texas Tribune, August 25, 2021, https://www.texastribune.org/2021/08/25/texas-covid-19-vaccine-mandates-ban-greg-abbott/. Joshua Fechter, “Gov. Greg Abbott Wanted State Lawmakers to Ban Mask Mandates in Public Schools. They Didn’t,” The Texas Tribune, September 7, 2021, https://www.texastribune.org/2021/09/07/texas-legislature-school-mask-mandates-abbott/.

↑ - 27

“Secretary Kirstjen M. Nielsen Announces Historic Action to Confront Illegal Immigration,” Homeland Security, December 20, 2018, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2018/12/20/secretary-nielsen-announces-historic-action-confront-illegal-immigration. Richard Gonzales, “US Is Rolling Out Its ‘Remain In Mexico’ Policy on Central American Asylum-Seekers,” NPR, January 25, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/01/24/688470513/u-s-plans-to-enforce-remain-in-mexico-policy-on-central-american-asylum-seekers. Richard Gonzales, “Trump Administration Begins ‘Remain in Mexico’ Policy, Sending Asylum-Seekers Back,” NPR, January 29, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/01/29/689819928/trump-administration-begins-remain-in-mexico-policy-sending-asylum-seekers-back. “All about the “Remain in Mexico” Policy,” Latin America Working Group, accessed October 14, 2019, https://www.lawg.org/all-about-the-remain-in-mexico-policy/.

↑ - 28

Molly O’Toole, “Trump Administration Appears to Violate Law in Forcing Asylum Seekers Back to Mexico, Officials Warn,” Los Angeles Times, August 28, 2019.

↑ - 29

Interview with the volunteer director of the Humanitarian Respite Center, July–August 2019.

↑ - 30

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (New York: Autonomedia, 2004), 7.

↑ - 31

Sivlia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (New York: Autonomedia, 2012), 65-66.

↑ - 32

Federici, Revolution at Point Zero, 65–66.

↑ - 33

Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera, 33–34.

↑ - 34

See U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “DHS-CBP-PIA-022 Border Surveillance Systems,” September 2018, https://www.dhs.gov/publication/border-surveillance-systems-bss; Eric Blum, “Further Reflection Surveillance Technology Boosts Border Security in Arizona,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, accessed July 18, 2019, https://www.cbp.gov/frontline/frontline-june-az-technology; George Joseph, “The Biometric Frontier: ‘Show Me Your Papers’ Becomes ‘Open Your Eyes’ as Border Sheriffs Expand Iris Surveillance,” The Intercept, July 8, 2017, https://theintercept.com/2017/07/08/border-sheriffs-iris-surveillance-biometrics/; Caitlin Dickerson, “US Government Plans to Collect DNA from Detained Immigrants,” New York Times, October 2, 2019.

↑ - 35

Sayak Valencia, Gore Capitalism, translated by John Pluecker (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2018), 9–12, 22.

↑ - 36

Valencia, Gore Capitalism, 12.

↑ - 37

bell hooks, Yearning: race, gender, and cultural politics (Toronto: Between the Lines, 1990), 145.

↑ - 38

hooks, Yearning, 145.

↑ - 39

hooks, Yearning, 145.

↑ - 40

As Judith Butler asks: “Who counts as human? Whose lives count as lives? . . . What makes for a grievable life?” Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2006), 20.

↑