Schools and Prisons

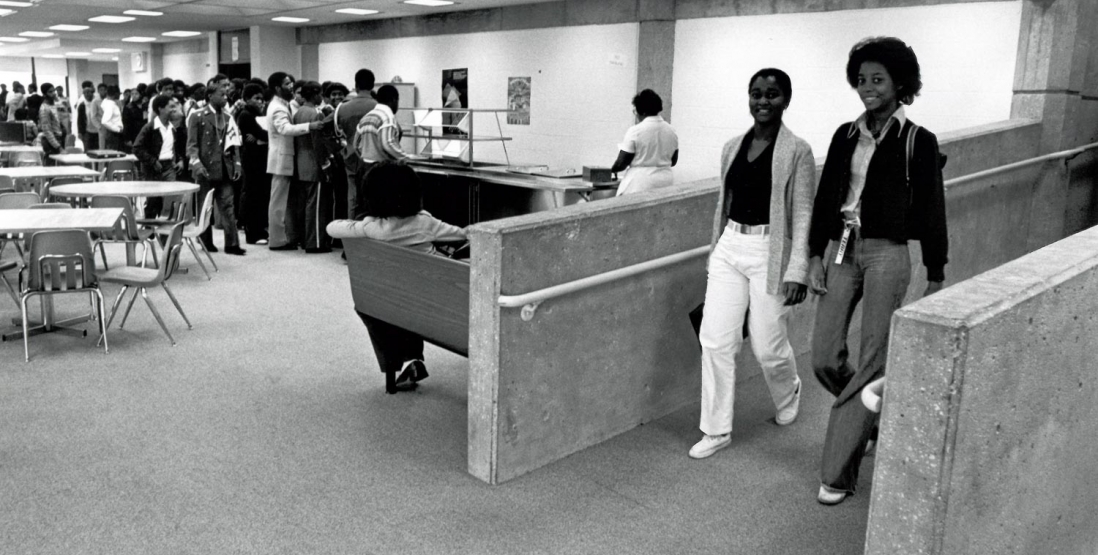

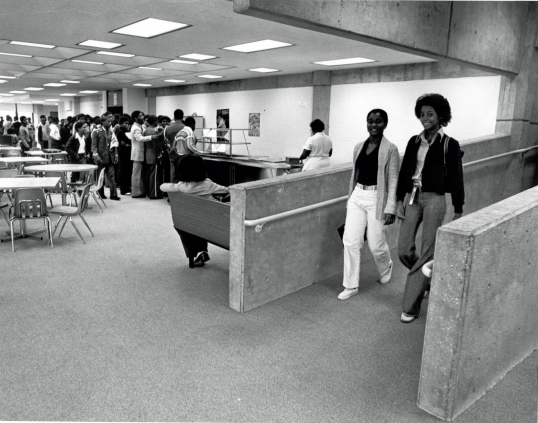

Former Dunbar High School cafeteria. n.d.

Sumner Museum, Washington, D.C. Public School Archives, Washington, D.C.The killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and others occurred when these black men and boys encountered police officers operating according to protocols that called for aggressive intervention against not only major crimes, but also small, everyday infractions, such as selling loose cigarettes. Order maintenance policing, including stop-and-frisk tactics, sets up confrontations that sometimes turn deadly. More often, its impact is less immediate. But by introducing youth and adults into the criminal justice system early and often, this mode of exercising state control over bodies and behavior in urban space leads to racially disparate impacts, initiating processes of mass incarceration and what Michelle Alexander calls the New Jim Crow.1

These practices have a corollary in schools, where order maintenance policing and steep penalties for minor infractions tend to push out students of color, deny them access to education, and in some cases initiate a criminal record that increases their likelihood of subsequent imprisonment. In the context of racial segregation and disparate levels of funding, hallway patrols and strict “zero tolerance” discipline lead to suspensions, expulsions, and dropouts. These set up poor black students for incarceration, drawing them into what has come to be called “the school-to-prison pipeline.”2

Education scholar Joan T. Wynne writes that with the emphasis on control and obedience that prevails in this context, schools

operate like prisons, where students of color—especially those forced to live in poverty by an economic system that demands there be “losers”—are daily maligned and rigidly controlled as though they already wore orange jumpsuits. … In these schools situated deep in the belly of most cities, the prime attribute desired for their marginalized students is obedience, not academic excellence. Obedience prepares them not just for prisons, but for the military and for low-paying jobs.3

The means of bodily and subjective regulation employed in what we might call pipeline schools exemplify some of the disciplinary mechanisms made famous through Michel Foucault’s analysis of prisons. In Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1979), Foucault noted that prisons were only the most extreme instrument of a broader disciplinary architecture, asking, “Is it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals, which all resemble prisons?”4 Schools have a deep history as disciplinary instruments.5 The normative and regulatory practices embedded in pedagogy scale up; schools shape entire populations. We can understand the school-to-prison pipeline as a contemporary moment in a longer history of biopolitical schooling.

In many ways, the policies that underlie the school-to-prison pipeline harken back to the “civilizing” discourse of early educators wanting to assimilate ethnic minorities into mainstream America. Public education in the United States was not considered obligatory upon the founding of the nation. It became a method of assimilation and a framework for teaching civic ideals as the immigrant population began to swell in the 1820s and 1830s, and as ideas of Manifest Destiny propelled western expansion and incorporation of new territories—and Native peoples—into the nation. Education scholar Donald Warren explains:

Schools represented a means to a greater purpose. They were to harmonize a diverse people, soften their antagonisms, and equip them to function as citizens in a changing society. In pursuing these goals, schooling in all its aspects became civic education. Curriculum, textbooks, teacher selection and preparation, and pedagogy required attention because they affected outcomes. So too did school architecture, classroom furniture, and basic policies on access, attendance, and school finance, the point being to fashion institutions whose effects on children would serve the nation’s republican aspirations.6

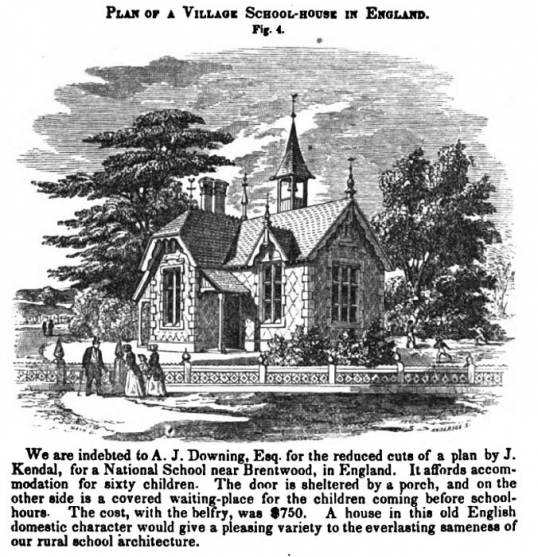

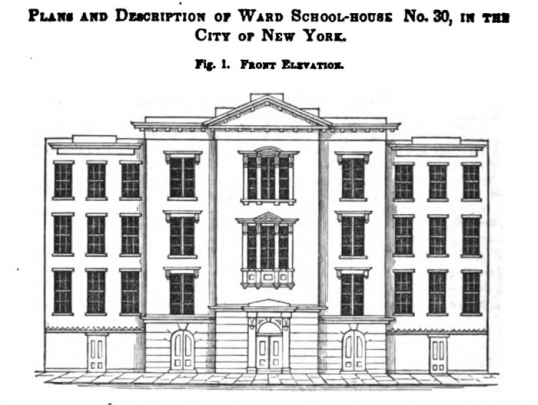

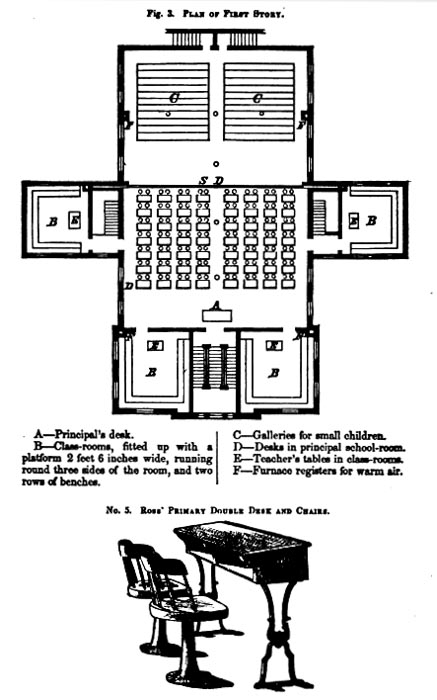

Policy-minded educators such as Horace Mann and Henry Barnard systemized and normalized public education by focusing on pedagogy, curriculum, and design. Barnard published School Architecture: Or, Contributions to the Improvements of School-houses in the United States in 1854. This survey of school conditions and pedagogical issues across a number of states highlighted the newest designs for school-houses and school furniture. The book traced an evolution from simple, one-room buildings to edifices that resembled the villas promoted by Andrew Jackson Downing to large, civic institutions that resembled castles. School design had become less domestic and more authoritative as it reflected growing civic idealism.

A Village School-house in England. Plan by J. Kendal.

Henry Barnard, School Architecture: Or, Contributions to the Improvements of School-houses in the United States (New York: A. S. Barnes & Co., 1854), 92.

Ward School-house No. 30, New York City, elevation. T. B. Jackson, architect. 1852.

Henry Barnard, School Architecture: Or, Contributions to the Improvements of School-houses in the United States (New York: A. S. Barnes & Co., 1854), 226.

Ward School-house No. 30, New York City, plan and furniture. 1852.

Henry Barnard, School Architecture: Or, Contributions to the Improvements of School-houses in the United States (New York: A. S. Barnes & Co., 1854), 229.

Hughes City High School, Cincinnati Ohio. 1853.

Henry Barnard, School Architecture: Or, Contributions to the Improvements of School-houses in the United States (New York: A. S. Barnes & Co., 1854), 260.

Students in these classrooms formed a captive audience. School designs promoted utilitarian concerns for order, control, and restriction of movement. Tables, chairs, and desks bolted to the floor discouraged lateral communication and other forms of community among students. “In a phrase that was used widely before the Civil War,” Warren notes, “the schools were to be ‘efficient and effective.’ They must husband human and material resources, and students must learn.”7

Education for African-Americans was minimal in the antebellum period, but after Emancipation, the Freedmen’s Bureau set up educational institutions, mainly in the South. Native Americans were sent to boarding schools in increasing numbers by the late 1800s as national expansion westward continued to encroach on their lands. Large waves of immigrants from Italy and Ireland in the late nineteenth century, meanwhile, propelled Anglo-Saxon Protestant fears about the national language, culture, and polity. Education for Negroes, Natives, Italians, and Irish taught the values of the dominant political class and assimilating students into the status quo. This approach exemplified what Paulo Freire would later describe in Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) as a colonialist system that addresses students by “treating them as unfortunates and by presenting for their emulation models from among the oppressors.”8

Schools were places where young members of these diverse populations left behind the comforts, familiarity, and customs of their home life, family, and cultural traditions. They normalized a narrow canon of thought, behavior, dress, and language while punishing divergence from cultural hegemony, at times through corporal discipline. This was particularly the case in many of the Indian boarding schools throughout the nation.9 Richard Henry Pratt derived the pedagogical aims of these schools from his military training and a prison experiment. Pratt believed that Native Americans principally lived a savage and uncivilized life, but could be saved through education. He had instructed Native American prisoners of war at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, several of whom went on to study at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, which was established in 1868 by the Freedmen’s Bureau to instruct emancipated slaves. In 1879, Pratt subsequently founded Carlisle Indian Industrial School in the military barracks in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

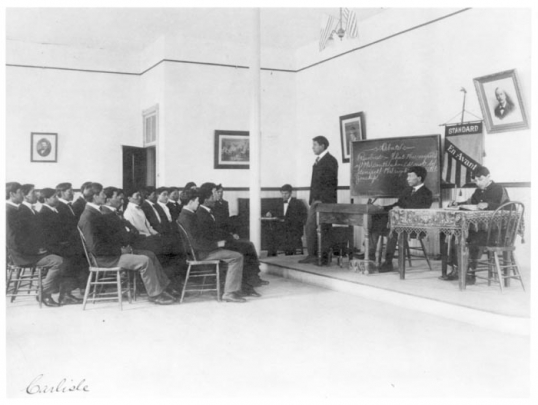

Men debating in class. Carlisle Indian Industrial School in former barracks. 1901.

Library of Congress.

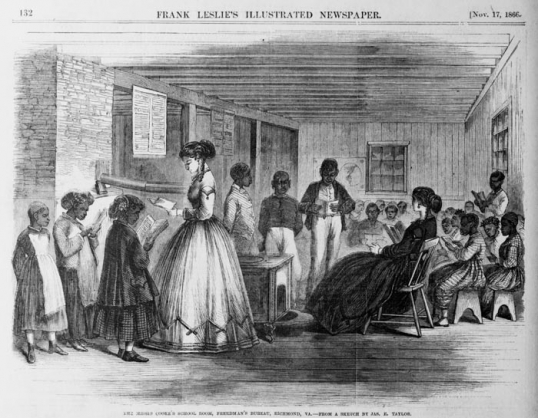

Miss Cooke’s School Room in Chimborazo Hospital, Freedmen’s Bureau, Richmond, Virginia.

Parker Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 17, 1866, 132. Library of Congress.

John Dewey would argue against such controlled, restrictive, and authoritarian environments in The School and Society (1899) and Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education (1916). Dewey promoted experiential learning and freedom of movement as a means for teachers to better understand the individuality of their pupils. In his view, restricted classrooms implied an “artificial uniformity” that was harmful to the learning process.10

What role does architecture play in the contemporary biopolitics of schooling? In building the school-to-prison pipeline? Public schools are still very much normative spaces, instruments for instilling conformity, obedience, and control in pupils rather than promoting Deweyan values of exploration and self-expression. This is particularly true for schools with a high percentage of black and Latino children, as these policies affect ethnic minorities, students with learning disabilities, LGBTQ students, and the poor especially heavily. School design, in an effort to be both efficient and economic, reinforces pedagogy oriented toward order and discipline. An increased culture of fear in educational facilities across the nation has also led to the criminalization of the school environment.

One path into this question of architecture’s role in the biopolitics of schooling is to consider two successive buildings that housed Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C. One design, completed in 1977 by Bryant & Bryant, a black architecture firm founded by two brothers trained at Howard University’s School of Architecture, was an open-plan high-rise high school constructed as part of the rebuilding of Washington, D.C. neighborhoods devastated in the 1968 riots. At the time of its completion, this brutalist building, then the most expensive public school built in the D.C. metropolitan area, was lauded for its innovative design. The project was a “breakthrough commission” for Bryant & Bryant, and the “comprehensive high school and community center was the largest prime architect/engineer design commission ever award[ed] to an African-American owned firm.”11 It was demolished after the construction of its replacement.

The successor design, completed in 2013 by the architecture firms Perkins Eastman and Moody Nolan, is a handsome and aspirational building of brick and glass. Nonetheless, it evokes Joan T. Wynne’s assertion that “the school to prison pipeline is in reality a prison to prison pipeline.”12 Security and surveillance practices associated with order maintenance schooling are an integral part of daily life at the new Dunbar, and they were part of the architectural brief for the building’s design.

There are many common positive attributes to the designs of both the 1977 and 2013 Dunbar High School facilities. Both employed a skylit atrium to flood the interior spaces with natural light: The former did this within the academic wing itself, while the latter building’s atrium is part of the entry sequence. Both buildings offered immense square footage to the student body: the 1977 Dunbar was a whopping 340,000 square feet and served 1,800 students. The 2013 version is 280,000 square feet, but only serves 600 students. In an effort to break up the massive scale of the buildings and to personalize the space for students, both the 1977 and 2013 concepts employed the use of academic “houses” (the 2013 plan calls them “academies”) to create a sense of belonging. The attributes are testaments to the aspirational nature of school design itself, and in both cases architects took care in attempting to respond to students’ environmental and psychological needs.

Current Dunbar High School skylit atrium, or “armory,” 2013.

Photo by author.

Current Dunbar High School armory with entrance vestibule in the background, 2013.

Photo by author.

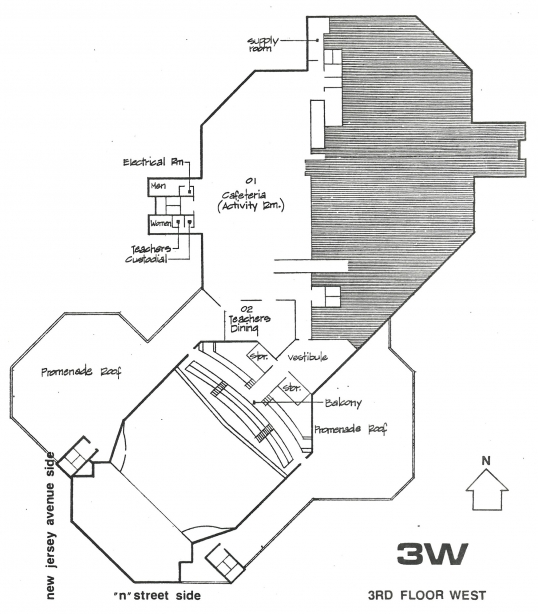

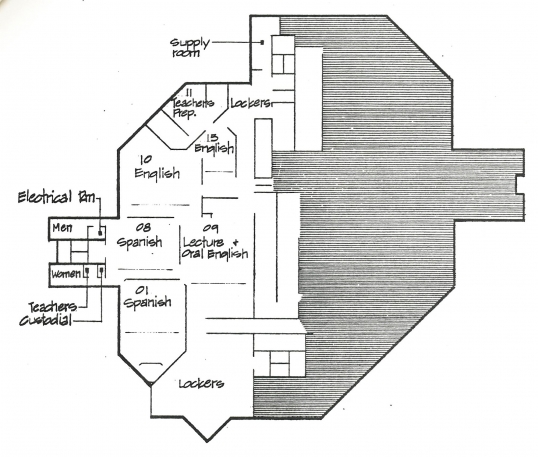

Sharp differences in the plans, however, are signs that schooling and architecture at Dunbar have shifted from a Dewey-like model to one focused on hierarchy, policing, and order maintenance. The 1977 building employed open classrooms on tiered mezzanines, while the current plan segregates different subjects through an L-shaped footprint composed of arts and recreation in one wing and classrooms in the other, arrayed along double-loaded corridors.

Former Dunbar High School, plan of third floor west.

Washington Board of Education Division of Buildings and Grounds, Dunbar Senior High School, April 1977. Sumner Museum, Washington, D.C. Public Schools Archives, Washington, D.C.

Former Dunbar High School, plan of third mezzanine west.

Washington Board of Education Division of Buildings and Grounds, Dunbar Senior High School, April 1977. Sumner Museum, Washington, D.C. Public Schools Archives, Washington, D.C.

Like many urban high schools with majority-minority populations, Dunbar today employs methods for enforcing order during the school day that promote obedience. A recent Architectural Record article describing the entry sequence paints an incomplete picture: “You ascend the broad steps to the entrance. Walking into a large skylit atrium, you find floor-to-ceiling windows opening to vistas of the surrounding residential neighborhood.”13 Between the broad entrance steps and the atrium, however, is a vestibule where the student is greeted by metal detectors, x-ray machines, and video surveillance. Additionally, video surveillance is omnipresent throughout the school itself—from the double-loaded corridors to the quiet reflective spaces situated with cozy armchairs overlooking glass expanses that reveal the neighborhood to the students. Many articles about the 2013 design highlight the fact that the school is open, light, and airy, with an abundance of wall space dedicated to fenestration. These considerations certainly give an impression of open civility to the outside world. In these moments, that could truly be beautiful and reflective for students, there is always an indication of mistrust—often felt by the presence of video surveillance. The school environment has been criminalized.

Dunbar High School main entrance, 2013.

Photo by author.

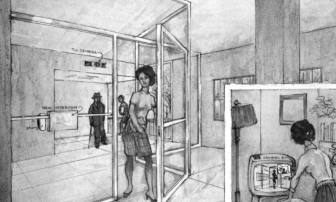

Dunbar High School vestibule. This area contains metal detectors, x-ray machines, and video surveillance. 2013.

Photo by author.

Fig. 15. Double-loaded corridor of the academic wing with video surveillance. 2013.

Photo by author.

Beginning in the 1990s, control and conformity became ritualistic, and security and surveillance became pervasive. The practice of security became a formalized, tedious, and dehumanizing ceremony not unlike what air travelers experience in the post-9/11 milieu. Some public schools adopted strict uniform policies. Students were required to carry see-through backpacks and walk through metal detectors on a daily basis. Administrators introduced police and school security officers. This trend was rising even before the school massacre at Columbine in 1999, but as school shootings have become more common, school safety measures have grown more complex. As John W. Whitehead, founder of the Rutherford Institute states, “Schools, aiming for greater security, transformed themselves into quasi-prisons, complete with surveillance cameras, metal detectors, police patrols, zero-tolerance policies, lockdowns, drug-sniffing dogs, and strip searches.”14 The District of Columbia Public School system employs both Metropolitan Police Officers and Security Officers who work for the Metropolitan police district through a contract, and all but two of the middle schools and high school have metal detectors.15

Working with Critical Exposure, a not-for-profit that teaches young people how to use photography to advocate for change in their schools, students in District of Columbia high schools described the impact that some of these measures have on their educations.

At Dunbar, measures such as these are overlaid onto more traditionally panoptic passive surveillance mechanisms. Project manager David Shirey of Perkins Eastman observed that the building is organized spatially around key sight lines, such as those that allow assistant principals to monitor corridors through the glass walls of their offices. Shirey noted that the firm had taken pains to promote passive rather than active security measures, so that “when you walk through there’s not a sense of ‘I’m being watched all the time’… [I]f we can kind of remove that idea, then you can remove one-half of what some call ‘the prison mentality.’”16

During the design of the current Dunbar high school, what Shirey calls the prison mentality was frequently associated with the building it replaced. More broadly, when I conducted research for my dissertation “Concrete Solutions: Architecture of Public High Schools During the ‘Urban Crisis,’” the school-as-prison metaphor came up countless times. I was investigating the motivations behind brutalist high school design in segregated black communities in three cities: Atlanta, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. Contemporary criticisms of the buildings were directed at the seemingly impenetrable exteriors that offered little in the way of pedestrian-level engagement with the street, few windows, and blocky, sculptural masses of buildings that did not respond to their neighborhood context. What else were these buildings besides prisons?

My dissertation research revealed that the buildings were not designed to punish students or to prepare them for penitentiary life. Quite the opposite. Educational policymakers, architectural consultants, planners, school boards, and community groups invested in alleviating problems of concentrated poverty, social inequity, and urban unrest worked in tandem to push the institution of education toward a more inclusive and inspiring condition. They saw the neighborhood school as an anchor institution for not only education, but also neighborhood improvement in the form of social, cultural, and recreational activities.

I have written elsewhere about the construction and design of Dunbar as part of a shift in black political empowerment manifest in a new attitude toward the built environment.17 The reappropriation of African-American history and culture, part and parcel of the Black Power movement, was exemplified by a new vision for the future based on citizen participation, autonomous neighborhoods, and avant-garde solutions to the problems that plagued black communities in cities. These solutions included the creation of large-scale, modern, urban high schools that were meant not only to educate, but also to stimulate stagnant or declining black urban centers like LeDroit Park, Bloomingdale, the U Street Corridor, and Shaw, the historically black neighborhoods that Dunbar served.

The Dunbar High School built in 1977 reflected a softer version of disciplinary design than prevails today. In its design, the need to control student behavior was substantially tempered by countervailing aspirations for empowerment and constructive engagement. Sight lines such as those in today’s Dunbar, which replaced the 1977 brutalist building, likewise embedded passive surveillance into schooling. Bryant & Bryant considered themselves “sensitive humanists” whose work reflected a “design empathy consonant with the environment and people to be served.”18 The open-plan vision of education at Dunbar was inspired in part by Dewey’s vision of responsive and democratic education.

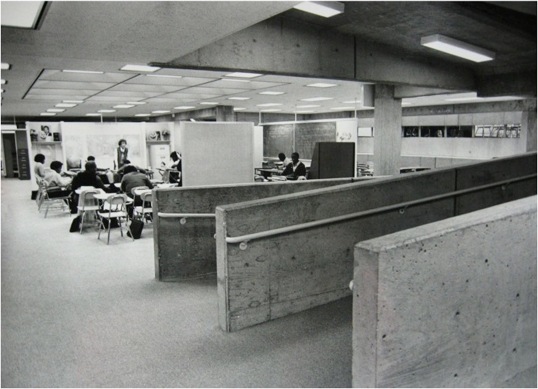

Experiential learning was a primary concern in the design of the 1977 Dunbar High School. The curriculum embraced the societal and cultural interests of the students. Afrocentricity was introduced into a curriculum that was previously based on a strict collegiate preparatory model. Hope for the open-plan classroom rested on the fact that the barriers among administrators, teachers, and students, so long normalized in a rigid hierarchy, would be eliminated along with classroom walls. Freedom and individuality would inform both pedagogy and learning spaces. The design was shaped in part by the concept of “defensible space” developed just a few years earlier by architect Oscar Newman. By eliminating hallways, the open plan prevented students from roaming during class in unappropriated corridors. The plan allowed for countless sight lines from one communally appropriated space to another so that administrators could observe student actions on mezzanines. These passive mechanisms of surveillance and territorialization were geared at supporting the goal of self-actualized learning in an open environment.

Former Dunbar High School cafeteria. n.d.

Sumner Museum, Washington, D.C. Public School Archives, Washington, D.C.

Former Dunbar High School classroom. n.d.

Sumner Museum, Washington, D.C. Public School Archives, Washington, D.C.

While open plan and brutalist buildings fell out of fashion in the 1980s, they continued to be used in a variety of communities across the nation. In Washington, D.C., the situation for Dunbar and many other educational facilities constructed in the 1970s was dire. School maintenance declined in relation to declining student enrollments. By the time I began my research on Dunbar in 2006, the school was in a terrible condition and harshly critiqued, particularly as plans for a new building emerged. One graduate of the 1977 Dunbar building, T. Harris, responded to a public criticism of his high school on the popular blog Ghosts of DC, underlining the school’s effectiveness:

During my tenure at this building referred to as a prison by those in opposition of it, I felt free and obtained a quality education… The open space environment did not impede my education in the least bit. […] The 1977 building became a prison when the idiot contractors came in and erected walls in the building. Many of the alumni who did the final walk-through of the building were horrified by the “cell block H” look as a result of the wall erection and the ridiculous yellow paint. The current principal has gone on record by stating that this building was a prison. That being the case he, by default, was the warden and crypt keeper.19

Harris referred to the fact that some educators at Dunbar rejected the open plan. Teachers re-arranged classrooms and created barriers by strategically locating bookcases and other movable furniture. In 2009, when the private firm Friends of Bedford took control of the school, administrators erected permanent walls where none had existed before, blocking sunlight that the exterior windows afforded the interior sections of the building.

Dunbar High School, interior wall, indicated by the number “7.” This was not part of the original design. 2010.

Photo by author.

The 1977 version of Dunbar High School was never meant to operate as a prison. The concepts behind its design stressed flexibility, connection, and liberal pedagogy rooted in cultivating self-policing autonomy in students. Indeed, nothing about an open-plan strategy in general suggests a prison. The prison-like aspects of the design were mainly attributed to the hard, brutalist exterior that was experienced from the outside. The image of the school as a prison derived from the building’s materiality, its massive shapes, and its lack of windows—a common trend toward energy-saving techniques in the 1970s. Metal detectors and other measures introduced decades later as order maintenance gained traction intensified this perception.

Dunbar High School, 1977.

Sumner Museum, Washington, D.C. Public Schools Archives, Washington, D.C.

As the case of Dunbar suggests, one way that our discipline can contribute to the project of revaluing black lives is through further research into the ways that architecture and architects help stage the pipeline and into telling the story of alternative approaches that promoted a more liberatory vision of schooling. The interior plan of the 1977 Dunbar High School was hopeful and visionary—it afforded students an environment that broke away from the traditional model and attempted to respond to student needs. Hard policing is much more evident in the 2013 design of the school, following national trends in the twenty-first century in which the ritualistic aspects of criminalizing the school environment undermine the culture of learning itself for minority students.

Related Material:

✓ Not peer-reviewed

Amber Wiley, “Schools and Prisons,” Aggregate 3 (March 2015), https://doi.org/10.53965/JFZU7212.

- 1

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2010). See also Alex Vitale, City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics (New York: New York University Press, 2008).

↑ - 2

American Civil Liberties Union, What Is the School-to-Prison Pipeline?, https://www.aclu.org/racial-justice/what-school-prison-pipeline. See also This American Life 538, Is This Working?, October 17, 2013, http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/538/is-this-working.

↑ - 3

Joan T. Wynne, “Foreword,” in Debra M. Pane and Tonette S. Rocco, eds., Transforming the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Lessons from the Classroom (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2014).

↑ - 4

See Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 228.

↑ - 5

See Thomas A. Markus, Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types (London and New York: Routledge, 1993); and Joseph M. Piro, “Foucault and the Architecture of Surveillance: Creating Regimes of Power in Schools, Shrines, and Society,” Educational Studies: A Journal of the American Educational Studies Association 44, no. 1 (2008): 30–46.

↑ - 6

Donald Warren, “Original Intents: Public Schools as Civic Education,” Theory Into Practice 27 (1988): 245.

↑ - 7

Warren, “Original Intents,” 247.

↑ - 8

Paulo Freire, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Seabury Press, 1970), 54.

↑ - 9

See Eric Margolis, “Looking at Discipline, Looking at Labour: Photographic Representations of Indian Boarding schools,” Visual Studies 19, no. 1 (2004): 72–96.

↑ - 10

John Dewey, Experience and Education (New York: Macmillan, 1938), 62.

↑ - 11

Bryant Mitchell Architects, “Portfolio,” accessed January 3, 2015, http://www.bryantmitchellarchitects.com/portfolio/index.htm.

↑ - 12

Wynne, “Foreword,” in Transforming the School-to-Prison Pipeline, ed. Pane and Rocco.

↑ - 13

Suzanne Stephens, “Dunbar Senior High School Perkins Eastman and Moody Nolan,” Architectural Record (January 2014), accessed January 20, 2015, http://archrecord.construction.com/projects/building_types_study/k-12/2014/1401-dunbar-senior-high-school-perkins-eastman-and-moody-nolan.asp.

↑ - 14

John W. Whitehead, “The Police State Mindset in Our Public Schools,” The Rutherford Institute, August 12, 2013, accessed January 8, 2015, https://www.rutherford.org/publications_resources/john_whiteheads _commentary/the_police_state_mindset_in_our_public_schools.

↑ - 15

Annie Gowen, “D.C. students use photography to protest school security,” Washington Post, April 4, 2013, accessed January 20, 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/dc-students-use-photography-to-protest-school-security/2013/04/04/e32bef48-8b44-11e2-9838-d62f083ba93f_story.html.

↑ - 16

Shirey as quoted in Alison Stewart, First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013), 288.

↑ - 17

For a more detailed history of the design of both the 1916 and 1977 manifestations of Dunbar High School, see Amber N. Wiley, “The Dunbar High School Dilemma: Architecture, Power, and African American Cultural Heritage,” Buildings & Landscapes 20, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 95–128.

↑ - 18

Bryant & Bryant, Architects and Planners, Washington, D.C., n.d., 3 and 5, American Institute of Architects Archives, Washington, D.C.

↑ - 19

Commenter T. Harris as quoted on Ghosts of DC, “Dunbar High School Opens With Problems,” August 20, 2013, accessed January 3, 2015, http://ghostsofdc.org/2013/08/20/dunbar-high-school-opens-with-problems/.

↑